“Ghost Customers”: How de-risking excludes the very people banks should protect

As usual with financial compliance, if you fail to spot real risk, there’s dire repercussions. In the case of blanket de-risking, there’s an even greater Pandora’s Box of implications beyond stalling financial access to low-risk entities – wrongly chasing the “ghost customers” who rely on those they bank with the most.

There’s already been a fair amount of criticism for regulators’ recommendation that financial institutions (FIs) need to narrow focus to high-risk customers; yes, that helps to stay in line with data protection laws, but fails to widen parameters to other threats that can ruin the regional or demographic reputations of legitimate customers that get left out in the cold.

Without that inclusion in the system, it only leads to something far scarier: the proliferation of the unregulated market where ignored customers will turn to, and providing greater shadow-cover for the criminals that lurk there.

A basis for blanket risk management

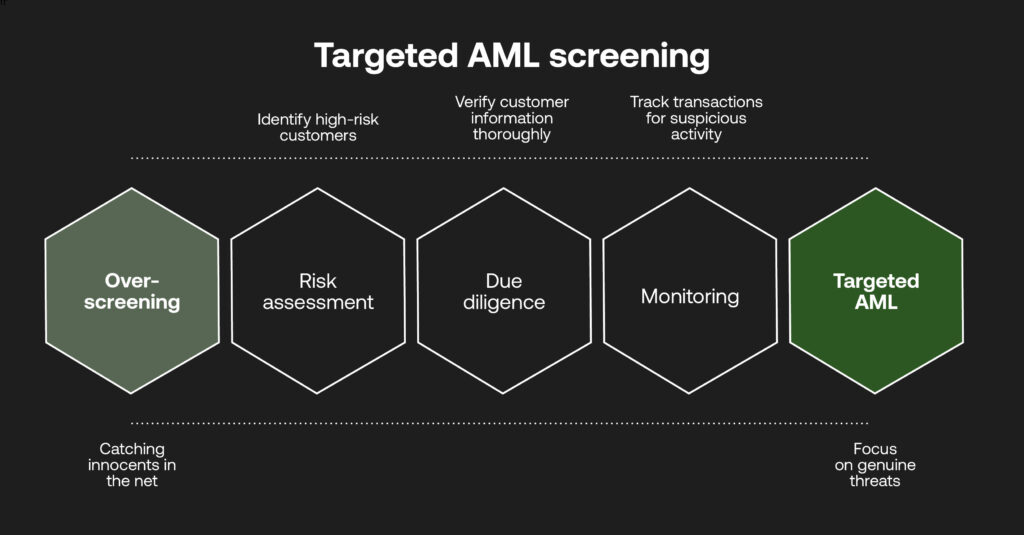

This job of ‘over-screening’ has been seen as a potential anti-money laundering (AML) technique for a long while. The World Bank has been regularly surveying de-risking practices heavily since 2016, highlighting its potentially harmful ramifications for real people using real banks for perfectly reasonable means.

The notion of de-risking is essentially whereby a financial party wishes to terminate or restrict a business agreement, relationship, or account with an individual or company, on the grounds of potential involvement with criminal risks. There may be multiple factors involved here: where lax AML at an institution cannot account for certain customer types, or if they operate in high-risk sectors (such as crypto exchanges) or geographies.

“If you cast a wide net, the better the chance of catching a launderer, only you’ll also catch others in a similar remit with absolutely no criminal history or ill intent.” says Kiearn Duggan, Head of Product at RelyComply. Fittingly, the aforementioned World Bank surveys indicated severely affected places, while a recent workshop of more than 600 private and public representatives deduced how over-compliance excludes low-risk people in Eastern and Southern Africa. The same people are often marginalised from the formal economy.

Forcing customers to turn away

This goes against providing financial inclusion which has been a cornerstone for progression in the industry. The inclusivity mission has opened the market to disruptive technologies able to provide access to anyone with a mobile, particularly in developing nations where financial literacy can be scarce. It’s created competition in spawning a healthy landscape of true innovation from traditional and newfound businesses.

Strict regulations (while necessary for safety) limit this approach for many, with blanket de-risking the unspoken-of phantom. Avoiding it can be damaging to costs, regulations and reputations on the institution’s side, but there’s plenty more at stake for the groups of individuals caught up in this cautionary move, no matter if these effects are unintentional:

- It breaks down trust: if an FI essentially ‘bans’ a legitimate customer without much explanation, those people will feel alienated and become a lost customer for the foreseeable future.

- It stalls business growth: with market reputations wrecked by poor customer retention, it affects turnover and the wider national economy.

- It identifies poor customer treatment: regulatory scrutiny, while strong, exists to maintain integrity in the system, but can in turn limit customer-centricity even more if FIs fail to adapt to changing market expectations and conditions.

- It evokes ethical issues: when the grounds for who is able to access finance are blurred, this becomes a human rights concern. In one example, de-risking has interrupted funding to NPOs in Syria due to conflict, therefore stalling necessary humanitarian care.

- It drives customers elsewhere: those left to finance’s fringes will seek out alternative methods or informal services where transactions are more opaque and the likelihood of exploitation is higher, especially in more volatile areas.

Are there smarter alternatives?

This is not to say that regulators are not looking to address the issues. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is the global forerunner in producing guidance for risk-based approaches to detecting financial crime, and in June 2025 released updated recommendations for facilitating financial inclusion in unserved or underserved markets. The European Banking Authority updated its risk factor guidelines in 2023 to establish effective AML risk controls where access to financial products can be limited.

“However, you cannot just pile one regulation on top of another. They are still considered a burden, and may not be able to help all businesses cover regional or cultural nuances; individuals’ financial needs must be heeded at more granular levels,” continues Duggan, “This is why professionals and their platforms must be risk-based in their approach to balance tricky compliance with more accurate AML methods that help keep the system inclusive.”

Moving away from blanket de–risking calls for far more comprehensive risk management, where onboarded customers, their behaviours, and transactions are investigated in real-time. Regulatory technology (RegTech) has come a long way in centralising data and means for identifying verification, monitoring and screening, and can provide hyper-specific alerts for enhanced due diligence that allow legitimate funds to flow freely, rather than excluding full industries or regions.

RegTech also acts as a facilitator in sharing pertinent data cross-sector, and in line with similarly tough data privacy laws. Transparency and collaboration is key for the financial system to become trustworthy and to instil greater AML safeguards across the board. We have already seen multiple instances whereby consumer pressure, legal ramifications and the financial industry have identified shortfalls in de-risking and pointed toward more accessible means of screening:

- In 2024, former Statistician-General of South Africa Pali Lehohla criticised banks’ openness and inconsistent metrics when accounts were closed arbitrarily as “reputational risk” in a wide-scale de-risking approach, also scrutinised by the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA). Its commissioner Unathi Kamlana suggested concrete reasons, and customers’ right to appeal for unfair treatment.

- In South Africa’s Ndudane vs Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) case, applicants asked for access to confidential information (suspicious transaction reports and risk management programmes) after having their bank accounts terminated, where their request was upheld in court.

Such instances indicate the urgency in housing audit trails for investigations, making it easily identifiable to regulators and intelligence centres where (and how) genuine risk is found and raised.

Better AML: No trick, all treat

“For AML to really do its job, investigations have to seek out the real threats from those that are just trying to go about their daily financial business,” says Duggan . “ Performing a generalised witch hunt in certain prone areas is a fool’s errand that lets actual crime flourish. We have the tools to focus on real illegal activity, share information and prosecute. But the proof is now in the action.”

De-risking can feel tempting to do given the threat of cybercrime and hefty fines, but it’s a losing battle in that it reduces the very inclusion the financial world is trying to solve. This is where protecting customers and FIs alike comes down to RegTech platforms that make risk-by-risk decision making that much faster and less cumbersome, and easier to cross-reference with the wider sector that matters.

It makes seemingly impossible compliance tasks possible in today’s real life data-heavy horror movie – unmasking the true villains, away from low-risk audiences that need to be treated fairly and respectfully, away from victimisation.