How dirty money still flows through banks despite AML regulations

Table of Contents

Money laundering remains one of the world’s most pervasive financial crimes, hiding in plain sight despite decades of anti-money laundering (AML) regulations. Popular culture may dramatise embezzled funds on TV, but the reality is far worse: an estimated $5 trillion is laundered through the world’s banks every year. While the numbers are staggering, they don’t capture the full human cost – lives damaged or destroyed through the illicit movement of money.

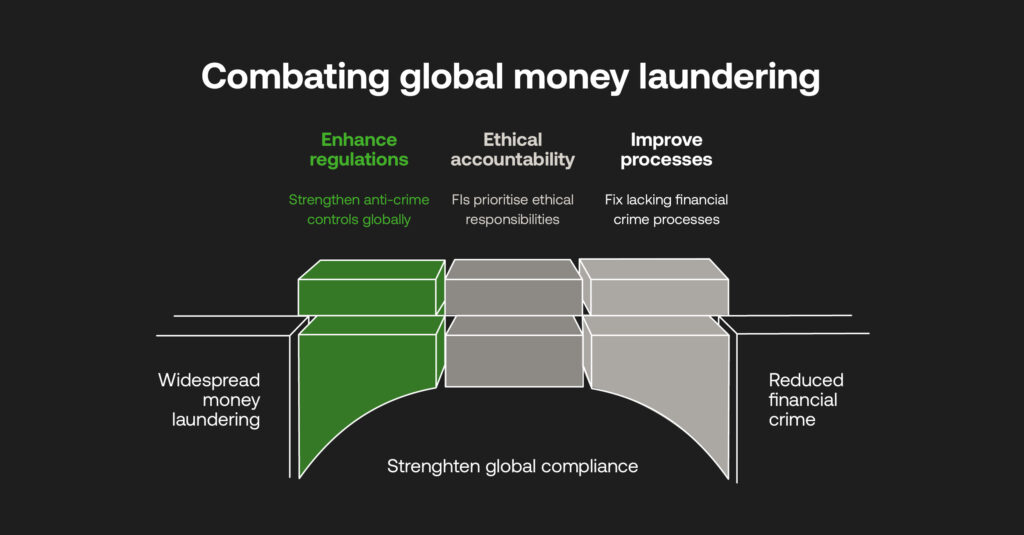

With the financial system used as the conduit to hide funds, how is it so prevalent, and who is ultimately responsible for criminality to flourish? Regulations do act as safeguards, trying to strengthen anti-crime controls and stop suffering. The problem may be that financial institutions’ (FIs) fixation on quarterly or annual budgets and the hunt for new customers outweighs the need to clamp down on every instance of laundering or terrorist financing.

There’s an ethical dilemma here around where accountability lies. A greater compliance culture may help get some of the way there. But only if the global system bands together to recognise and fix lacking financial crime processes that ensure dirty money and its dire knock-on effects continue unpunished.

The growing stage for financial criminals

There’s an idea that money laundering involves smart accountants pushing funds into offshore accounts in far-off islands, with no victims other than duped tax registries or huge financial companies. This glosses over the fact that proceeds are the result of heinous crimes that tragically claim human lives: the financing of weapons of mass destruction for terrorists, or the trafficking of vulnerable people in vast, organised crime rings.

Emotional and social fractures result from personally-targeted crimes that are, in many cases, financially motivated. Romance scams and identity thefts can destroy victims’ trust in other people and claim their entire life savings. These are tricky areas to govern between governments, financial institutions and their customers. So despite developments in data protection worldwide, criminals use breached data to impersonate real people without their knowing.

These networks are extremely tough to detect, often coordinated across social channels, data providers and scattered financial houses. The worry is the speed with which digitisation has granted these fraudsters even greater tools to penetrate the system. GenerativeAI and deepfakes increase the scale of fabricated online personas or can bypass biometric ID verifications, and the blockchain is prone to exploitation by launderers through unregulated cryptocurrency and other digital assets.

Criminality grows through insecure know your customer (KYC) checks or lax customer data privacy laws. South Africa is already one of the world’s largest offenders for data breaches worldwide; the saddening truth is that much of the population’s ID details will already be circulating on the dark web.

Municipal-level corruption: The growing frontline

Another way financial institutions and authorities are blindsided to exploitation is due to preconceived notions around corruption. In South Africa particularly, laundering, extortion, and cartel financing is tied to jurisdictional crime that often goes unaccounted for in anti-money laundering (AML) compliance. This feels foolish when it so often kickstarts state capture that has been prevalent in the nation, even at the highest levels of society.

Such cases bring the reputations of FIs heavily into question. These criminals still bank with someone. In some cases, the banks knowingly keep them on as customers. If there are no consequences and concrete prosecutions, criminals will feel they can continue getting away with it easily. Protecting legitimate customers is just as paramount when lowering crime and boosting trust are cornerstones for avoiding reputational damage.

Banking on ethics: The reputational risks of inaction

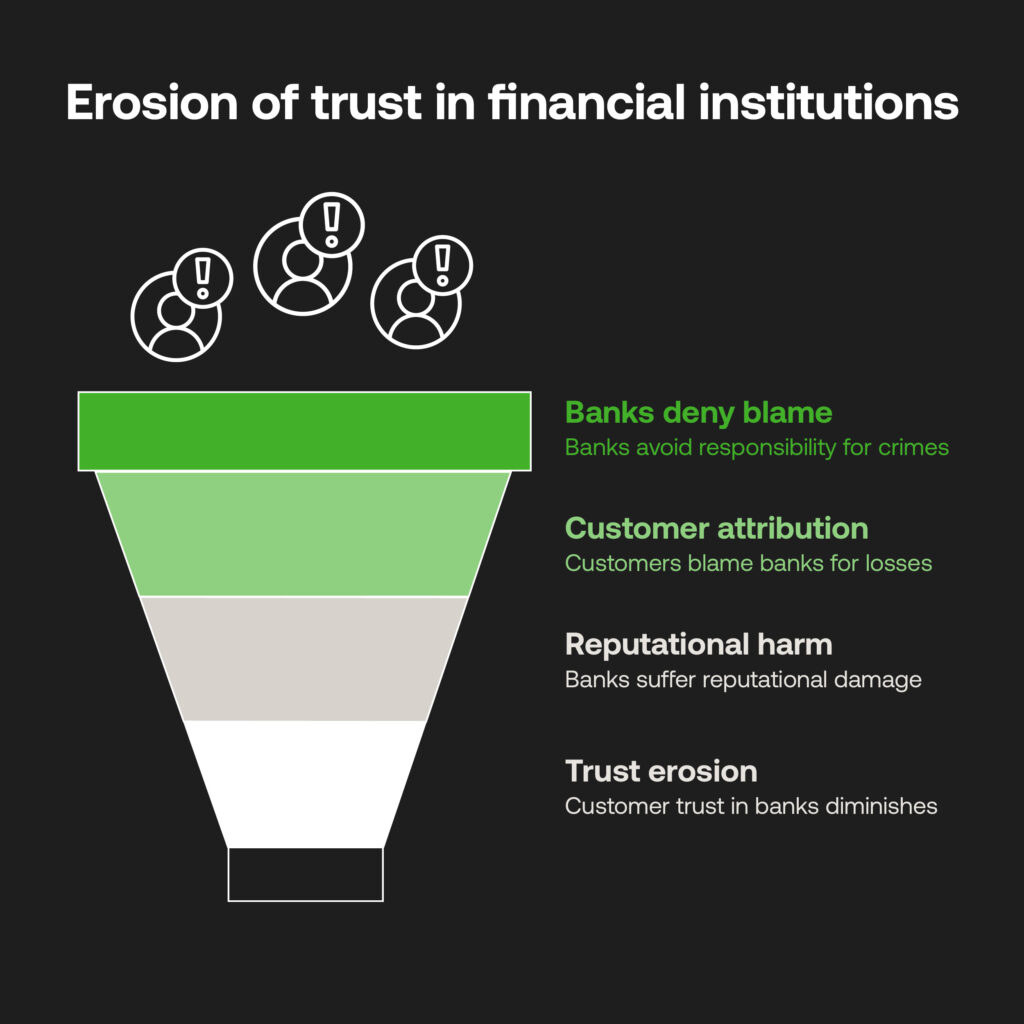

One main reason for customers’ tentative relationship with FIs is mixed perceptions over where fault lies as a result of these crimes. Customer attribution may be due to banks not accepting any blame or compensating for victims’ personal losses – particularly for romance scam victims or similar instances of sensitive information being handed over to con artists.

Some of these crimes may have occurred despite no fault in a bank’s internal processes. It harms reputations nonetheless. Acquiring new customers is costly and reliant on trusted relationships which FIs cannot build well if they do not acknowledge the faults of the financial system they exist in and show ethical consideration to prospective and existing customers. It’s understandable if they are put off by news stories of AML fines and data breaches, or if they are first-hand victims of crime, which banks need to demonstrate.

Unfortunately, this does not happen. There’s a continued pattern in FIs letting some criminality exist under their noses. An accepted fraud threshold is relied upon rather than total net-zero elimination, due to it being cheaper. It not only shows a purposeful lack of regard to complete AML or KYC, but also morally fails to recognise the human cost.

Can regulation really help?

At the moment, financial crime enforcement sits in a grey area between banks and police forces at local and federal levels, made more complex given global AML recommendations that incentivise private companies to ‘take on’ dubious law enforcement roles. Responsibility is blurred, and it is tough to determine who is at fault for missing or mis-reporting money laundering alerts. If there was a centralised global intelligence agency utilising shared data, there’s further questions around who would govern it and be liable to potential breaches.

AML frameworks were already a product of necessity in the 1980s, where law enforcement was perceived as unable to handle the extent of financial crime. Today’s digital age feels like another tipping edge requiring actionable regulation, rather than simply writing more rules into a guidebook. In which case, robust, standardised protocols may be the answer to build bridges between various players in the financial ecosystem. By sharing intel and using industry-leading technology to identify criminality and report data to relevant authorities for potential prosecution, a more proactive and collaborative approach can be cemented to help maintain sector-wide integrity.

The role of compliance technology in restoring accountability

Regulatory architecture is not shifting as fast as criminal typologies, and banks and fintechs, (traditionally opposing each other as competition) have been reluctant to share data. Individual FIs are also tailoring their own detection systems rather than relying on burgeoning industry-wide solutions. It’s clearly an ongoing challenge to adopt a unified AML approach that applies to every diversified financial provider in every country, despite the efforts of regional and global watchdogs, but they are improving as we speak.

Advanced regulatory technology (RegTech) is providing a lifeline here. Designed by experts and utilising AI-driven automations for transaction monitoring, end-to-end platforms such as RelyComply turn check-box compliance into real-time financial crime detection and risk reporting. Partnering with RegTechs allows low-risk payments and entities to continue accessing necessary financial products, all at lower costs to banks and fintechs. In maintaining that risk-based approach it shows a dedication to investigating real crime, prioritising people over profit.

So while a fractured and complex regulatory twilight zone may still be assisting dirty money to hide in the businesses we all bank with, clarified legislation and tech-first thinking can help foster collaboration that fills these gaps and leads to genuine repercussions for financial criminals. With some accountability identified, trust in the financial world can only grow, and FIs can resolutely contribute to a safer digital future for all.

Disclaimer

This article is intended for educational purposes and reflects information correct at the time of publishing, which is subject to change and cannot guarantee accurate, timely or reliable information for use in future cases.