South Africa’s property market exposes AML risks

Luxury real estate has long been synonymous with risk. From purchasing offshore residences for tax avoidance to the seizure of properties from sanctioned individuals, housing is a hotbed of anti-money laundering (AML) focus, with criminals hiding in an industry integral to everyone, everywhere.

The industry is complex even before cross-border activity is considered. Ownership structures are not standardised, nor are rules for estate agents, developers, legal businesses and mortgage lending practices. Highly bewildering is South Africa’s story of alleged criminal Nicole Johnson’s ability to purchase an apartment in a wealthy area while incarcerated, facing 100 charges and denied bail. Concealing financial ties, she was able to bypass verification using unregistered developers. No ensuing triggers were raised along the system that should have stopped this from happening from the get-go.

With so many moving parts, such criminals have been able to find multiple loopholes even with increasing scrutiny from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to validate property entities as accountable institutions obligated to surface and report financial crime. Here, we’ll attempt to identify what the systemic challenges are, and where key lessons from the Nicole Johnson case study can be found to avoid similar failures in other African markets.

Property AML in South Africa explained

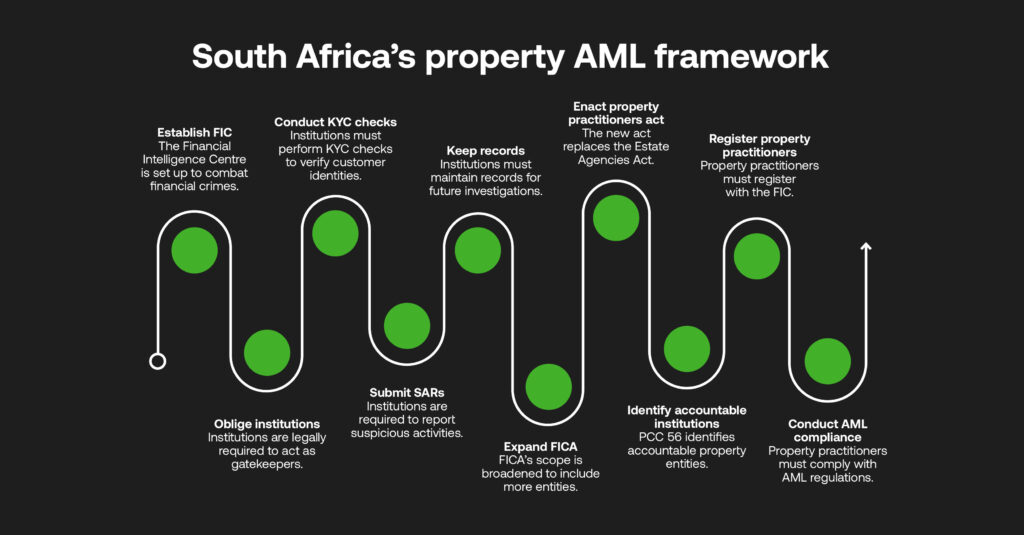

South Africa’s property AML framework has hinged on the Financial Intelligence Centre Act (FICA) since 2001. Its purpose was simple: to set up the Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) in the wake of terrorist financing and activity to stop nefarious actors washing their laundered funds through the country’s economy.

It legally obliges institutions to act as gatekeepers to maintain the integrity of the financial system, to register with the FIC, and conduct know your customer (KYC) checks, risk assessment, confirm source of funds, submit suspicious activity reports (SARs), and keep records for future investigations. FICA initially applied to banks; it has since increased in the past few years to many non-banking financial service companies.

Schedule 1 of FICA attempts to pin down accountable institutions as defined by the activities performed by the entity, beyond the legal form of the entity itself. Estate agents come under this banner, as defined in the Estate Agencies Act––which has since been repealed and replaced in February 2022 to become the Property Practitioners Act, including a wider definition for accountable property entities.

In November that year, a “soft law” piece of guidance entitled Public Compliance Communication (PCC) 56 identified that those registered as estate agents under the former Estate Agencies Act were still accountable institutions, while post-repeal “property practitioners” (including developers that perform previously defined estate agent activity) must be registered with the FIC and conduct full AML compliance.

Who is responsible for scanning property transactions?

Under FICA, a range of sector parties hold AML roles in identifying suspicious activity and making sure it’s stopped as early as possible, including:

- Estate agents: the first line of defense to raise suspicions for cash-based or large transaction property purchases.

- Conveyancers: the next level responsible for KYC, enhanced due diligence, and risk assessments for alerted flags.

- Banks: complex accounts such as trusts are within their duty, alongside additional due diligence and reporting capabilities required to understand customers in great depth.

- Legal representatives: involved in background checks to determine source of funds before a sale agreement should be signed.

- Developers: even if using affiliated agents, unregistered developers not ‘acting as an estate agent’ are potential loopholes for launderers, as is the case of Nicole Johnson.

The Nicole Johnson case: where systems fail

The makeup of the property system involving many bodies, regulations, and necessary precautions may sound complex, but there were multiple alarm bells in the case of Nicole Johnson which, instead, was fairly straightforward in its structuring.

Public information around Johnson – even through a simple Google search – should have raised eyebrows about her connections, even before the current prison sentence. She was able to find grey areas in the legislation, utilising willful developers unregistered with FIC, cash transfers, an unbonded deal without bank financing, and client confidentiality protection.

There was no KYC or risk assessment, and the enforcement gap may be to blame. In this instance, it alerts to a failure in the property system regulation that developers are not forced to claim they perform the action of estate agents and can slip under the net. Lax authorities may distance themselves by ‘deputising’ AML-ready financial companies as quasi-law enforcement when it’s the state’s role to reprimand known criminals.

Already, South Africa has a fairly small centralised pool of institutions (such as part of the NPA or tax divisions at law firms) to attempt to hold back the highly sophisticated and globally networked criminal underworld. Instead, the system needs cross-sector coordination to make any AML defence effective against such a force-intelligence over bureaucracy, and proactive detection rather than mandatory tickboxes.

Real estate’s continual AML challenges

As this example shows, widespread AML has still not been achieved to protect the property market from illicit funds, and there are multiple underlying hurdles that contribute.

Limited resources at SMEs

The way the financial ecosystem exists today is highly diverse, featuring specifically tailored products from small firms without the compliance budgets of huge multinational banks. Not all accommodate a base-level of compliance tooling, likewise for small conveyancers and estate agents.

Ultimate Beneficial Ownership (UBO)… and beyond

South Africa’s Companies Act defines a UBO as anyone with a minimum of 5% ownership of an entity, and tracking them through complex business structures is extremely difficult involving shell companies, trusts (registered provincially and fairly inaccessible), and opaque shareholding information very limited to the public in South Africa. Even when available, UBO information is handled at the behest of the monitored entity.

Technology gaps

Without continual KYC, the automated detection of high-risk transactional activity and adverse media, or SAR reporting made simple to the FIC, the entire chain responsible for AML is hindered.

Enforcement culture

It’s problematic when responsible bodies are siloed and expecting financial crime prevention to be handled elsewhere. A nationwide shift must involve greater public-private collaboration and data sharing to spot and raise suspicious behaviour before it infiltrates the system.

Privacy vs public good

There’s a delicate balance at play when reporting suspicious entities, where the current system is not working for those that do play by the rules. If it did, there would be more prosecutions resulting from more transparent knowledge into criminal activity and chasing those committing offences.

Lessons for Africa

South Africa’s experience in this case study, and given its strides toward de-listing from FATF’s greylist, should serve as an example that proactive AML measures in the property market should be conducted before getting nationwide financial systems into hot water with the global regulator.

1. Follow documented guidance

In most cases, regulations already exist as to how to best conduct AML at real estate offices, property management businesses, financial institutions, legal practices, and more accountable institutions under FATF. Effective action for proper enforcement is what lacks: where maintaining clear objectives and successes per business is needed, aligned to global and regional compliance laws.

2. Conduct education and training

Property practitioners should be well aware of their obligations under AML laws, while frequent training programmes for employees and assistance from industry professionals can instil readiness of compliance checks (which should be continually monitored by regulators, even at smaller accountable institutions). With awareness of criminal repercussions and AML best practices – seeing South Africa’s gaps as an example – made applicable to local contexts, compliance culture gets built.

3. Employ shared services and create a dialogue

Technical compliance needs to be simplified, and this comes as a result of shared platforms and public-private partnerships. RegTech providers can become first-person partners with AML knowledge and solutions to benefit a range of accountable property businesses, regulators, and financial institutions, making transactional behaviour data sharing timely, efficient, and flexible to future threats. Platforms can bring necessary parties together and create a more robust frontline of AML defense.

4. Define the roles of centralised data registries

UBOs, trusts, shell companies, and deeds are all complicated, inaccessible parts of property and pose problems when national registries are not able to identify inner workings of businesses. Nations and agencies should consider public registers, or non-public databases for regulatory and enforcement needs.

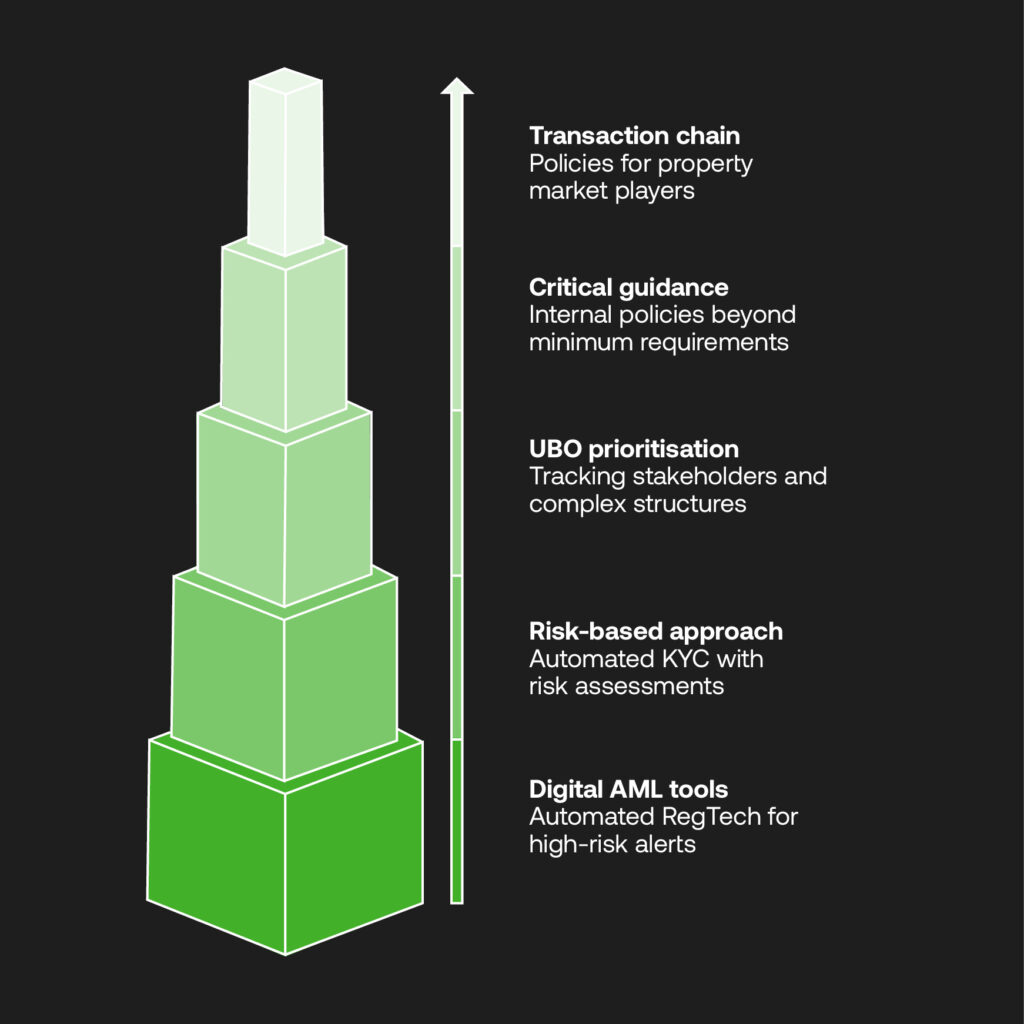

Within these parameters, compliance teams for accountable businesses can start to think critically about actionable steps to futureproof their property-based AML:

- Understanding the transaction chain: ensure internal policies cover the bases for the property market’s major players – estate agents, conveyancers, developers, banks, and legal practices.

- Following critical guidance: FICA and PCC 56 showcase how nationwide rules can be applied to accountable practitioners, but internal policies beyond these minimum requirements are paramount too.

- Prioritise UBOs: key stakeholders and complex structures like shell companies and trusts need to be tracked to understand who’s truly behind transactional activity.

- Become risk-based: automated KYC and due diligence is bettered by business-identified risk assessments and implemented thresholds to catch the alerts that matter, where small oversights provide criminal loopholes.

- Invest in digital AML tools: spotting high-risk alerts hinges on automated RegTech that can cost-effectively cover gaps in manual monitoring to stay attuned to changing criminal typologies.

The importance of proactivity today

The property sector will always be an attractive prospect to criminals. South Africa’s high-profile news shows this, but more importantly the failures created by unmandated responsibilities for developers, as well as other loopholes that could catch out every connected entity tasked with stopping illicit fund flows.

To draw any positive conclusions, it marks another wake up call for regulators, property market participants, and tech providers to work more strongly together. With greater AML compliance knowledge and the technical capability to instill it sector-wide, criminality can be stamped out at the earliest instance. The world’s financial ecosystem counts on smart partnerships to maintain its integrity, and not allow flourishing criminals to win.