The role of AI assistants: Fighting gender bias in technology

“Siri, don’t just help me, warn me!”

It’s Women Month. Let’s discuss those with the quietest, less-celebrated voices that actually help many aspects of our lives: ever-listening AI assistants that are always obeying and, strangely, almost almost female. Why is this the case?

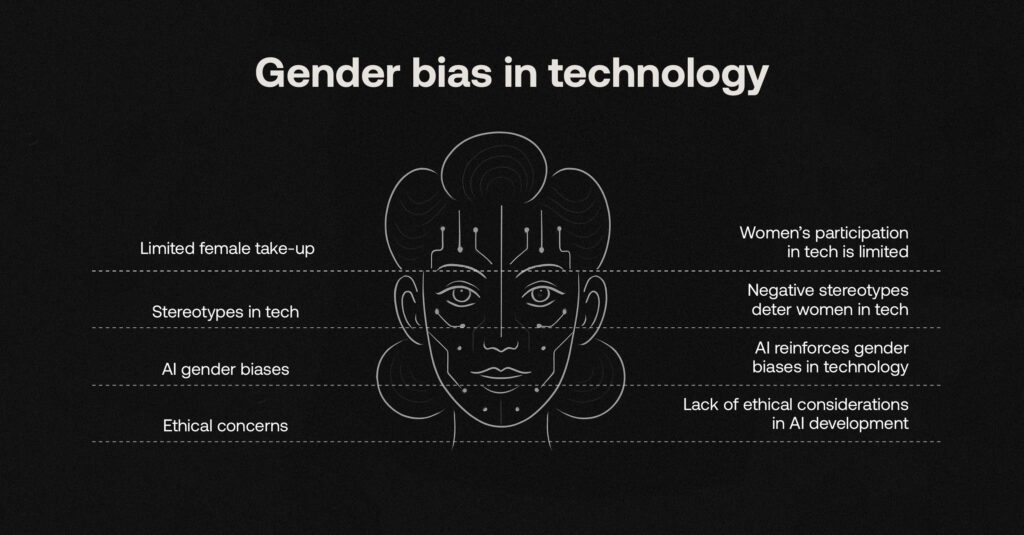

As a technology company that champions the careers and growth of all our employees, RelyComply is highly aware of stereotypes that pepper our industry: a largely inaccessible world with computer science niches made famous by jockeying, controversial dominant males portrayed in everyday news or popular culture (The Social Network, as a prime example). It’s true that a quarter of female students are put off of careers within the industry too. In part, this could be down to a gender bias that AI assistants like Siri and Alexa subtly promote––the woman as a passive voice––albeit them being well-intentioned as ‘friendly helpers’.

As AI usage grows, we see this rocky road not only reinforced by AI, but the platforms that utilise it every day. AI technology needs to be smart, and an active and just participant assisting our decisions regardless of identifiers. This concerns every sector that builds applications with AI as a vital factor; platforms must have a voice with human-like intelligence and ethical concerns for fairness to prevail, with financial technology very much involved.

Is AI warping what we know of the world, and ourselves?

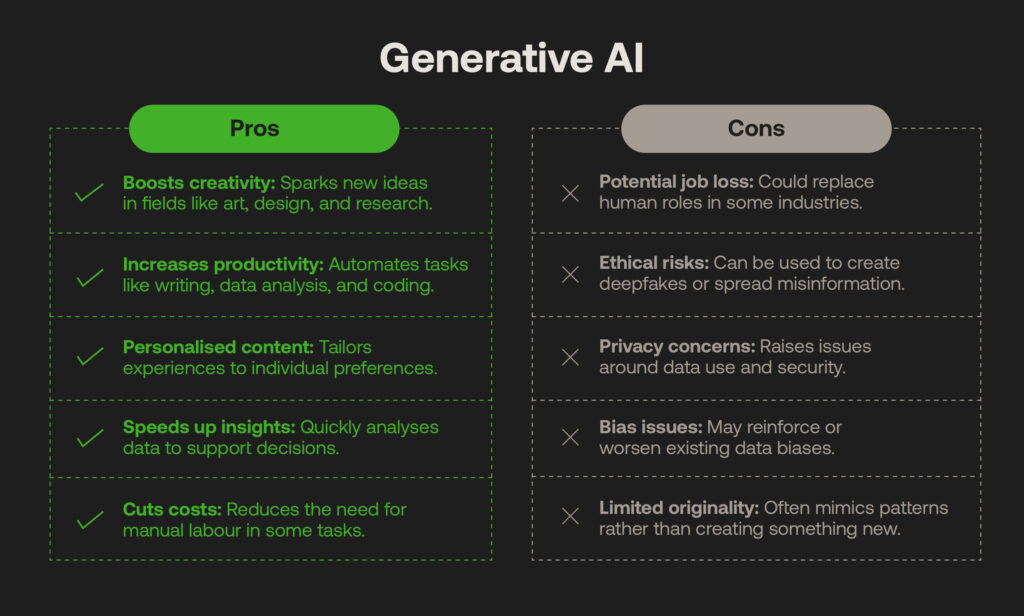

There have been a few worrying trends around Generative AI’s (GenAI) proliferation. A common theme is the technology’s time-saving effectiveness, sparking the idea of ‘replacing’ job roles rather than alleviating dull, manual tasks as intended. It risks an I, Robot ‘man vs machine mentality, which, while an extreme case, still takes away from AI’s thoughtful life-changing solutions, such as spotting diseases early, managing energy efficiency, or discovering criminal behaviour hiding in plain sight.

We cannot avoid controversial GenAI use cases. Deepfakes technology skews the very idea of identity and truth to spread hateful content online or to hack into user accounts by bypassing biometric authentication. The loss of autonomy over our identities, gendered or otherwise, is a significant concern; Denmark has recently led the vanguard in ensuring everyone’s right to “their own body, facial features and voice” to combat this crime.

“Human beings can be run through the digital copy machine and be misused for all sorts of purposes and I’m not willing to accept that.” – Danish culture minister, Jakob Engel-Schmidt

Standards for utilising AI are considerably on government agendas, namely the EU’s AI Act. We see these much-needed regulations affecting the way financial systems run. They are under scrutiny for their ethical training and implementation of AI to spot anomalies and risk (which could indeed misrepresent data through bias, gendered or otherwise). Reining in AI technology stems from the way we train algorithms. AI outputs will continue reinforcing this learning if presented with historical datasets skewed to cognitive human biases.

Where ‘supportive’ AI datasets fuel gender bias

The association of obedience linked to the female voice is an enduring problem. The UN notes how popular language models gender certain ‘service role’ job titles, women “nurses” and men “scientists”. There’s also a correlation between gendered AI voice assistants and men’s and women’s reactive behaviours; a study by John Hopkins engineers found underlying biases towards ‘supportive’ feminine voices while gender-neutral assistants did not feature hostile interactions or interruptions for intentional mistakes (usually from male participants). This identifies that AI systems are built to ‘parrot’ – to take orders in a friendly and responsive way that obeys what inputs it gets.

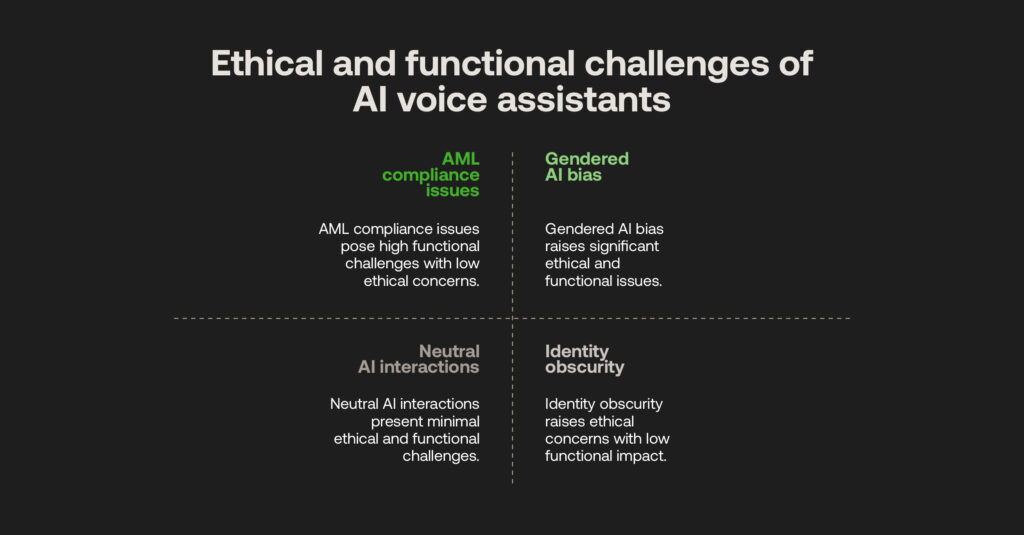

This sets a dangerous precedent for systems, as they cannot challenge poor human decision-making. This is particularly true in the financial world. ‘Silent’ AML compliance platforms will obey the rules they have been set and miss critical risks accordingly. User-based risk thresholds can demonstrate historical biases around certain entities’ demographics (particularly if not representative of a diverse compliance team), and AI models can be trained against biased algorithms discriminating against gender. A lack of transparency for how anti-fincrime systems store and use customer data within their AI practices also takes away agency from customers.

“Thoughtful design – especially in how these agents portray gender – is essential to ensure effective user support without promoting harmful stereotypes. Addressing these biases in voice assistance and AI will ultimately help us create a more equitable digital and social environment.” – Amama Mahmood (John Hopkins study)

Technologies must therefore be built with humanitarian oversight. Considerations made in establishing AI systems extends to the end user and the very real world. In financial technology’s case, lending platforms that do not victimise between ‘male’ or ‘female’ professions or backgrounds that seek a personal or business loan, or using chatbots that are less generalised and representative of customer concerns.

Creating co-operative forces for societal change

Automated AI technology can be a true force for good in the right hands, mainly when utilised under ethical considerations swiftly introduced to law. When developments continue regarding how women are perceived as ‘helpers,’ AI platforms can become active agents rather than submissive, set up without bias, and become accountable voices to achieve their goals alongside their human counterparts.

Modern RegTech aims to revolutionise this path with balancing AI and human-led approaches in a transparent way auditable to customers and regulators alike. At RelyComply, we’ve ensured that there is accountability from both sides, utilising machine learning to rank highly suspicious behaviours and singling out alerts on a scale that a human could not, which more accurately discovers ‘actual crime’ quickly following enhanced due diligence in the analyst’s hand. We also employ ‘explainability’ techniques to demonstrate how our models are trained: what datasets are used, and what results are achieved.

When each of the model’s opinions and decisions gets interrogated, this shows a 50/50 commitment from both parties in the detection and investigation process; the super-human results gained from the platform’s own intelligence and the platform user’s interpretation of the outcomes. Man and machine are jointly responsible for the ethical use of AML compliance, using customer data in line with privacy laws, and duly informing and improving gaps in each other’s capabilities to empower quality investigations that are cooperative rather than simply taking orders.

Our platform has been built to foster better decision-making through automation and industry-best AI accountability, where we see these raised issues of cognitive biases providing positive transformation to the technology sector. Suppose regulations and legislation can help the financial industry change the AI narrative. In that case, forward-thinking platforms play an even more effective role in crime detection and reduce gendered stereotypes.

Technology is not going anywhere; it is crucial for societal progress. With ethical oversight becoming the norm, we’re all heading in the right direction.