A guide to managing financial crime risk amid UK regulatory shifts

Executive summary: navigating the convergence of strategy, policy, and enforcement

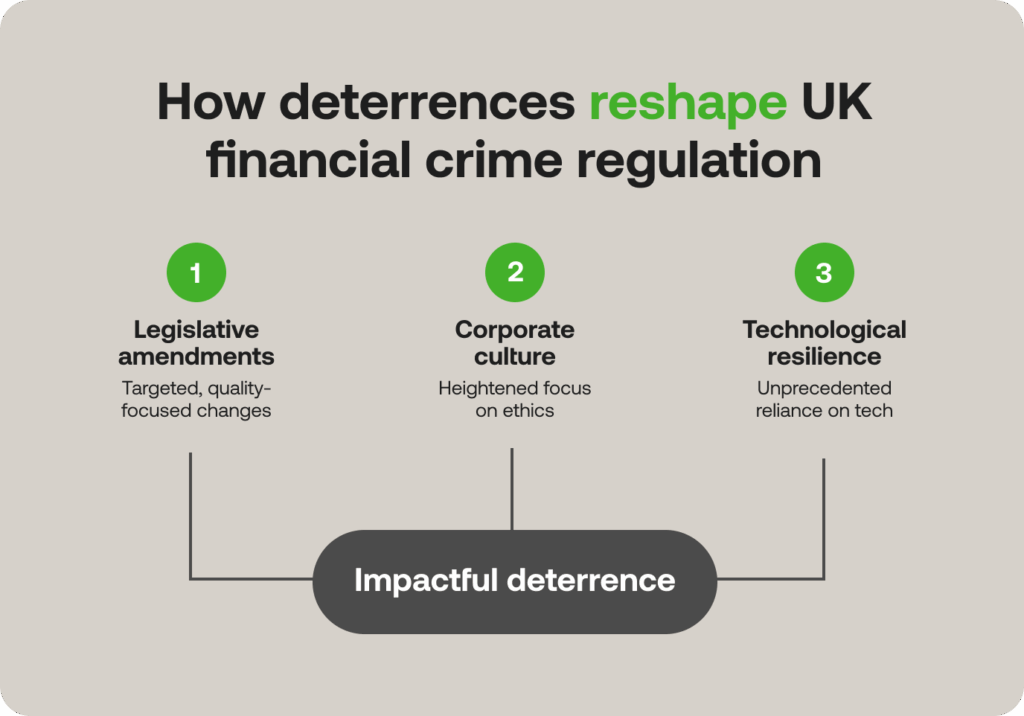

The landscape of financial crime risk amid regulatory shifts in the UK has fundamentally transformed in 2025. This is not a period of piecemeal adjustments but a strategic realignment where a reactive, volume-based compliance model is replaced by a proactive, data-driven, and judgment-based one. The core of this new paradigm is “impactful deterrence,” a strategy where regulators prioritise quality over quantity in enforcement. This shift manifests in three key areas: a new era of targeted legislative amendments, a heightened focus on corporate culture, and an unprecedented reliance on technological resilience. For UK compliance leaders, this guide serves as a roadmap to understand these profound changes and to align their strategies with the evolving regulatory expectations. The focus must now be building robust, technically compliant, operationally resilient, and culturally sound internal frameworks.

Chapter 1: The UK’s evolving strategic regulatory compass

The UK’s principal financial regulators, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), have clarified their strategic direction for the mid-2020s, with a clear focus on becoming “smarter” and more effective. This strategic pivot is more than an internal efficiency project; it fundamentally redefines the relationship between regulators and regulated firms, particularly in the context of financial crime.

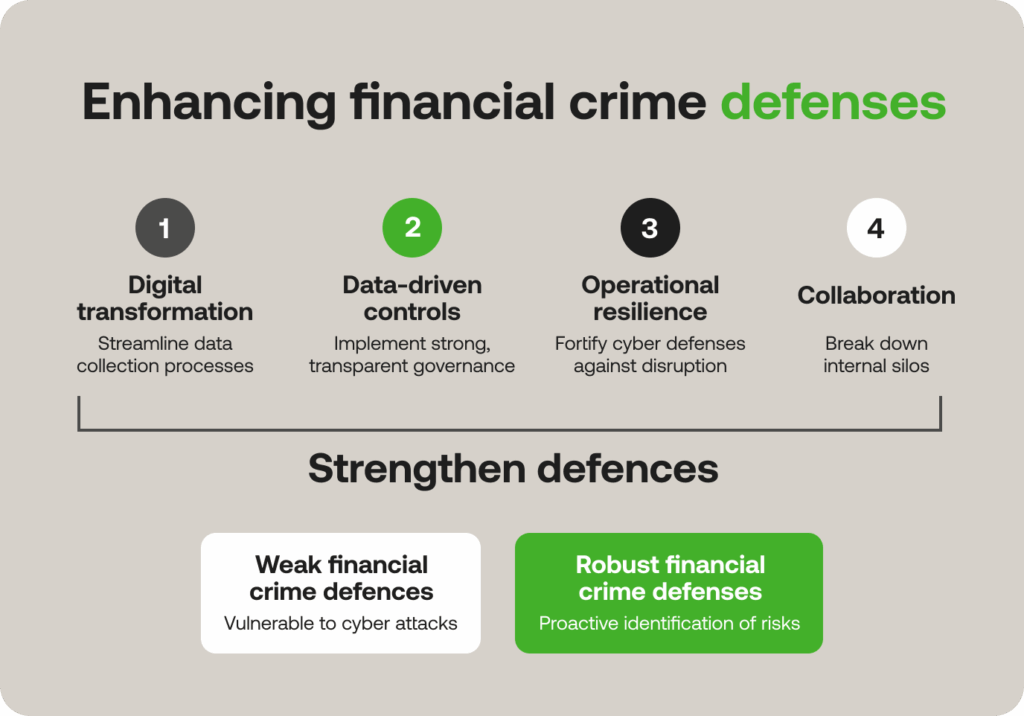

The FCA’s 2025/26 Annual Work Programme and its broader 2025-2030 Strategy centre on four strategic priorities: becoming a smarter regulator, supporting growth, helping consumers, and fighting financial crime.1 These priorities are deeply interconnected. The FCA is undertaking a significant internal digitisation program to fight financial crime more effectively. This includes streamlining data collection, enhancing the supervision model, and improving the use of intelligence and data to identify and act on harm.1 The FCA plans to simplify triage processes to focus on higher-risk cases, reduce administrative burden on lower-risk ones, and expand its use of data and intelligence to target the riskiest firms and individuals.1

This digital transformation creates a new, data-driven regulatory dynamic. The FCA’s ambition to implement “less intensive supervision for those demonstrably seeking to do the right thing” 3 is not a concession but a quid pro quo. The regulator is building a “new data-led detection capability to bring together multiple data sets”.2 This allows it to move beyond passive, report-based supervision and proactively identify financial crime risks. As a result, firms that can demonstrate strong, data-driven controls and transparent governance will be viewed favourably. Conversely, firms with antiquated systems or poor data governance may be subject to more intense scrutiny and a greater regulatory burden. This reframes investment in data infrastructure and analytics from a mere cost of compliance to a strategic imperative that can directly reduce regulatory pressure and enhance a firm’s market standing.

Concurrently, the PRA’s 2025/26 Business Plan reinforces its primary objectives of ensuring the safety and soundness of the banking and insurance sectors while advancing its new secondary objective on “competitiveness and growth”.5 This plan’s significant focus is on operational and cyber resilience. The PRA intends to consult on new policies for Information and Communication Technology (ICT) risk management and will test firms’ resilience to evolving cyber threats through threat-led penetration testing.5

The PRA’s prudential focus on operational resilience directly and profoundly impacts a firm’s anti-financial crime defences. Financial crime, particularly fraud and money laundering, increasingly leverages technological vulnerabilities and cyber-attacks. By strengthening a firm’s operational and cyber defences against disruption, the PRA is, by extension, fortifying the firm’s ability to prevent and detect financial crime. This highlights a critical convergence of prudential and financial crime risk. A failure to manage ICT risk can directly facilitate a financial crime, as evidenced by the FCA’s fine on Barclays for “failing to organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively with adequate risk management systems in respect of its account opening procedures”.6 This interconnectedness requires financial crime compliance leaders to break down internal silos and collaborate closely with their counterparts in operational risk, IT, and cybersecurity to ensure a holistic and robust defense framework.

Chapter 2: Dissecting legislative and policy changes (2025/2026 horizon)

The legislative and policy agenda for 2025 and 2026 demonstrates a precise movement away from a rigid, prescriptive rule-based regime toward one that is more risk-based and reliant on a firm’s judgment. This shift is most evident in the proposed amendments to the Money Laundering Regulations and the FCA’s new rules on non-financial misconduct.

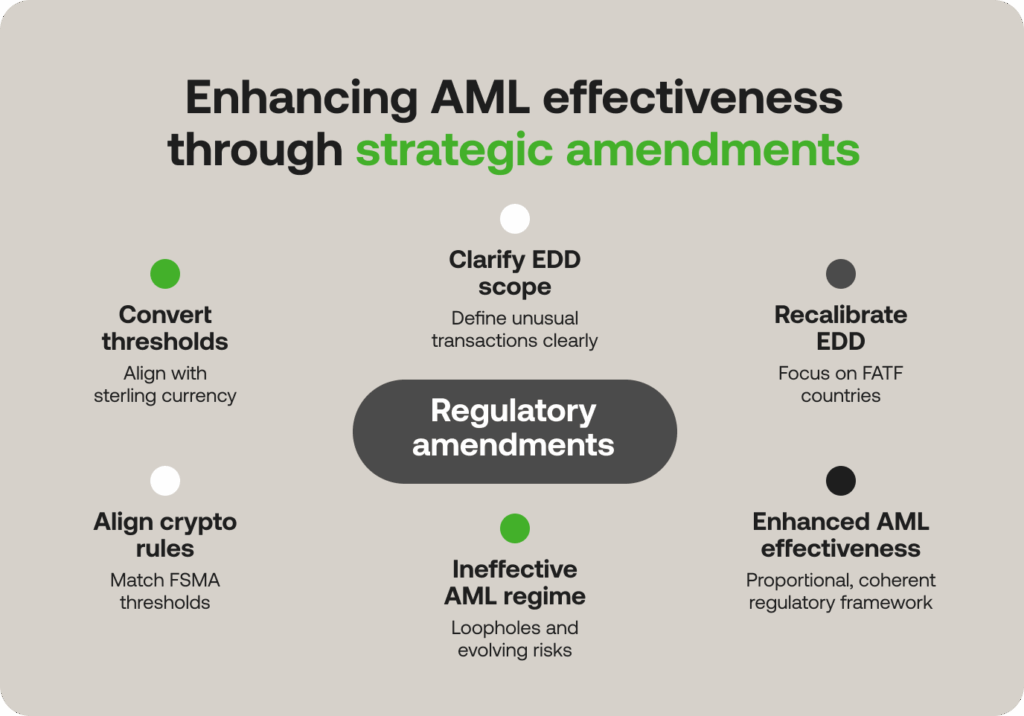

Targeted amendments to the Money Laundering Regulations: recalibrating proportionality

HM Treasury’s draft Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing (Amendment and Miscellaneous Provision) Regulations 2025 7 represent a targeted effort to improve the effectiveness of the UK’s AML regime. The amendments are designed to close loopholes, enhance proportionality, and account for evolving risks.7 The most significant change is the recalibration of Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD) requirements. The draft Statutory Instrument (SI) narrows the obligation for EDD to apply only to “FATF call for action countries” instead of all “high-risk third countries”.7 Furthermore, it clarifies that EDD is required only for “unusually complex or unusually large” transactions relative to what is typical for a sector or transaction.7

While these changes appear to be a regulatory relaxation, they are a strategic move that places a greater onus on a firm’s internal risk assessment and judgment. By removing a prescriptive rule, the regulator demands that firms develop and document a robust and defensible framework for what constitutes an “unusually complex or substantial” transaction. The burden of proof has shifted. A compliance defence for a failure can no longer simply be “the rule didn’t apply to us.” It must be “our well-governed, data-driven framework concluded that this was not an ‘unusual’ transaction, and here is the evidence to support that conclusion.” This forces compliance leaders to invest in sophisticated data analysis and internal governance to justify their decision-making.Other notable amendments include converting all monetary thresholds from euros to sterling 7, and aligning the registration and change in control thresholds for cryptoasset firms with the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA).7 This streamlining aims to reduce ambiguity and create a more coherent regulatory framework.

The FCA’s new rules on non-financial misconduct: a cultural bellwether

The FCA’s Consultation Paper CP25/18 outlines a significant step in tackling non-financial misconduct (NFM).10 The new rules, which come into effect on 1 September 2026, will explicitly extend NFM regulations to non-bank financial services firms, clarifying that serious misconduct such as bullying, harassment, and violence in the workplace constitutes a breach of regulatory rules.10

The FCA’s focus on NFM is not merely about social policy but a strategic regulatory move. Based on its survey data, which found that firms often lack appropriate governance to deal with NFM, the FCA operates on the premise that a poor internal culture is a leading indicator of systemic weakness.12 A firm that tolerates misconduct in one area is likely to have deficiencies in its broader control and governance environment, which increases the risk of financial crime. This is because a lack of integrity, openness, and cooperation with regulators, as seen in the fine against James Edward Staley for breaching individual and senior manager conduct rules 6, is a direct cultural failure that can create an environment where financial crime can flourish. Therefore, compliance leaders must formally integrate NFM into their risk frameworks. A failure to address cultural issues will be seen as a human resources problem and a direct breach of conduct rules that could also indicate broader systemic failings in financial crime controls.

Chapter 3: Data-driven enforcement: trends and implications

Analysis of the 2025 enforcement data from the FCA and PRA reveals a clear shift in regulatory strategy from a volume-based approach to one focused on high-impact outcomes. This is the essence of “impactful deterrence.”

FCA and PRA enforcement in 2025: the rise of “Impactful Deterrence”

A review of the FCA’s enforcement data for 2024/25 shows a paradoxical trend: the number of open enforcement operations fell from 188 to 130, yet the total value of confiscation orders and penalties increased significantly.6 confiscation orders rose from £0.9 million to £6.88 million.13 The FCA’s “impactful deterrence” strategy is clearly being implemented by focusing on a smaller number of more significant cases.1 The regulator concentrates its resources on the public interest and systemic risk.

This means a decrease in enforcement actions does not signal a less active or more lenient regulator; it signals a more strategic and, arguably, more dangerous one. The investigations launched are likely more systemic and result in much higher penalties, as seen in the case against Barclays. The FCA is no longer just targeting individuals or small firms; it is pursuing significant, complex cases that send a clear message to the entire industry.

Case study: The Barclays fines – A blueprint for failure

The FCA’s £42 million fine against Barclays in July 2025 serves as a powerful case study for this new era of enforcement.14 The fine was issued for two instances of failing to manage financial crime risks. The first case involved Barclays Bank UK PLC, which failed to adequately verify a client’s authorisation to hold client money, leading to an increased risk of funds being misappropriated.14 The second, and larger, fine was levied against Barclays Bank PLC for its poor management of money laundering risks associated with a corporate customer, Stunt & Co.14The FCA’s Final Notice clarifies that the failings were not isolated incidents but a systemic breakdown of controls. Barclays failed to gather enough information at the start of the relationship and perform proper ongoing monitoring.14 Crucially, the bank’s response was inadequate even after law enforcement raised suspicions of money laundering and informed them of a police raid on the customer.14 The FCA viewed these as fundamental failures to “organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively with adequate risk management systems”.6 This case is a powerful lesson for compliance leaders: proactive, continuous, and judgment-based risk management is now a non-negotiable expectation. A passive, reactive approach to financial crime will not be tolerated, resulting in substantial penalties.

Table 1: Key FCA & PRA Fines in 2025

Chapter 4: The international context and horizon scanning

The UK’s financial crime agenda is not an isolated domestic policy but part of a complex global framework. The actions of international bodies like the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the newly formed EU Anti-Money-Laundering Authority (AMLA) will significantly influence the direction of UK regulation.

FATF: global standards and UK alignment

The FATF, the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog, continues to shape international standards explicitly referenced in UK policy. In June 2025, the FATF updated its Recommendation 16, also known as the “Travel Rule,” to improve the transparency and security of cross-border payments.16 The changes clarify responsibilities within the payment chain, standardise information requirements for peer-to-peer payments over a specific threshold, and require financial institutions to use new technologies to protect against fraud.16

This move is mirrored in the UK’s domestic policy. HM Treasury’s amendments to the MLRs, particularly the narrowing of EDD to “FATF call for action countries” 8, are a direct effort to align the UK’s framework with evolving international standards. This demonstrates that the UK’s regulatory framework remains intrinsically linked to global developments despite Brexit. For compliance leaders, effective horizon scanning must include actively monitoring FATF updates and anticipating their eventual incorporation into UK legislative frameworks.

The rise of AMLA and its implications for UK firms

The formal establishment of the European Anti-Money-Laundering Authority (AMLA) on 1 July 2025 is a significant development in the global regulatory landscape.17 While AMLA has no direct jurisdiction over UK firms, its creation will profoundly affect any UK firm with EU-facing operations. AMLA’s 2025 Work Programme signals a high priority on the crypto sector and intends to supervise 40 financial institutions directly.17

AMLA’s creation will set a de facto standard for best practices and a benchmark for regulatory scrutiny within the EU.17 For global firms, operating with two radically different compliance frameworks—one for the UK and one for the EU—is impractical and inefficient. AMLA’s actions will influence market expectations, legal precedent, and the overall trajectory of European financial crime regulation. This will inevitably have ripple effects on the UK’s competitive landscape. Therefore, UK compliance leaders, particularly those with a European footprint, cannot ignore AMLA’s work. Its actions will set a new benchmark for an effective AML/CFT program in Europe. UK firms must keep pace to remain competitive and avoid regulatory arbitrage.

Chapter 5: Strategic imperatives for the modern compliance leader

The relentless pace of regulatory change is not an insurmountable burden but an opportunity for firms that can adapt strategically. The UK’s new regulatory paradigm demands a shift from reactive, tick-box compliance to a proactive, judgment-driven, and culturally integrated approach.

Actionable recommendations

- 1. Invest in Data Infrastructure and Analytics: The FCA’s move towards a data-led supervisory model means that a firm’s ability to demonstrate a robust, real-time understanding of its risk profile is a strategic asset. Compliance leaders should conduct an internal audit of their data infrastructure and analytics capabilities, identifying areas for investment to reduce manual reporting and enhance proactive risk identification.

- 2. Redefine and Document Your Risk-Based Approach: The MLR amendments place a greater emphasis on a firm’s judgment, so compliance leaders must review their internal risk assessments and due diligence frameworks. This is an opportunity to move beyond simplistic rules and create a mature, well-documented, and defensible framework for judgmental decisions, particularly regarding what constitutes “unusually complex or large” transactions.

- 3. Prioritise Cultural Governance: The FCA’s focus on non-financial misconduct should be seen as a bellwether for its broader expectations of corporate culture. Compliance and HR leaders must collaborate to integrate NFM into the firm’s cultural and compliance frameworks, recognising that a failure to manage misconduct can signal a systemic weakness that increases financial crime risk.

- 4. Proactive Horizon Scanning: Effective compliance in this new environment requires a forward-looking perspective. Firms should establish a dedicated function to monitor UK regulators and international bodies like FATF and AMLA. Anticipating how global standards will be incorporated into UK law is critical to strategic planning.

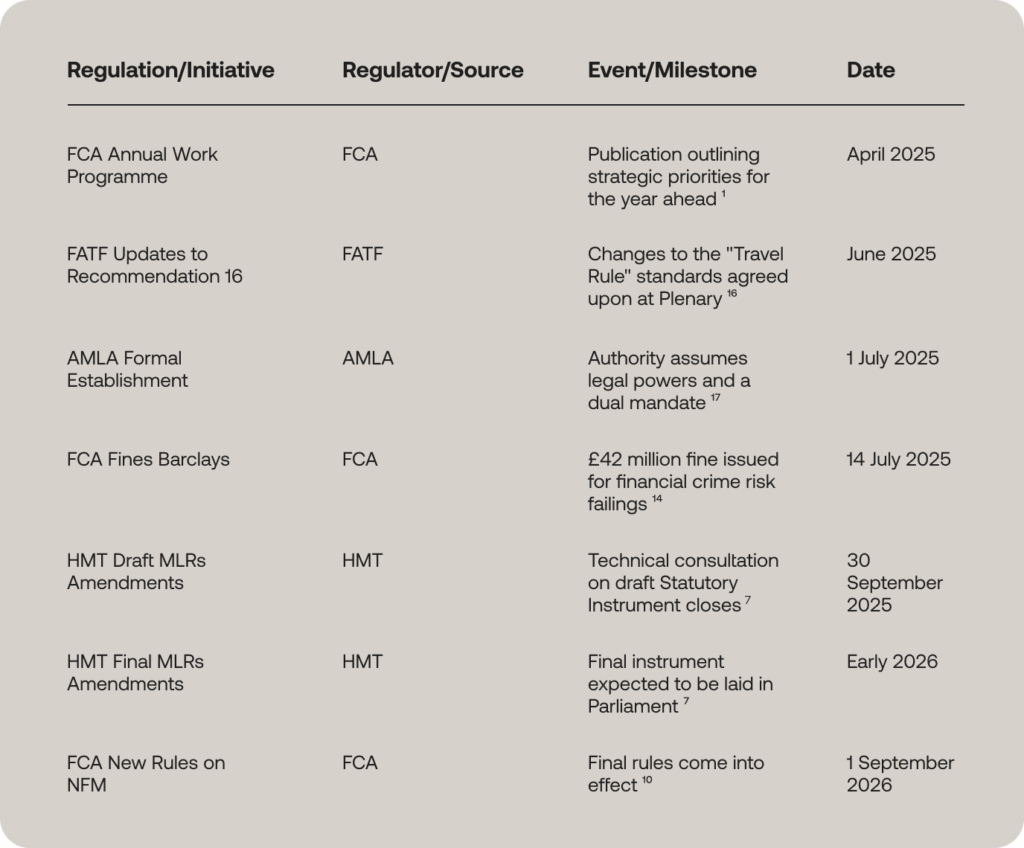

Table 2: Key Regulatory and Legislative Timelines (2025-2026)