Digital ID debate: the UK pushes back on the Brit Card

Preventing financial crime is something we’re always working on at RelyComply, and now with the launch into the UK, we have started to hear from Brits about the implementation of the digital ID and what that means for them. Financial services have always identified people through KYC, KYB, and AML processes – but what happens when this extends beyond financial services? This is what we explore in this article.

Identity fraud is becoming unavoidable. The digital routes criminals take to obtain information are growing, reinventing methods that have long managed to catch vulnerable consumers unawares (such as phishing and financial or romantic scams), and also to fuel money mulling and laundering efforts. This type of fraud accounts for the majority of investigations handled by the National Fraud Database in the UK, which reached unprecedented levels in the first half of 2025 with over 217,000 cases filed.

Battling identity-based crime is on the agenda, but causes troubles alongside the crimes themselves. The proposal of the UK’s Digital ID ‘Brit Card’ is a governmental action to clamp down on illegitimate identification documents, and has been a political pawn for two decades. In the nation’s current time of political precariousness, the public’s attitude toward who we trust with information, how it’s used, and how to access it is still up in the air, prompting the question: how can nations justly implement ID verification that acts on behalf of their citizens?

The intention vs the reality

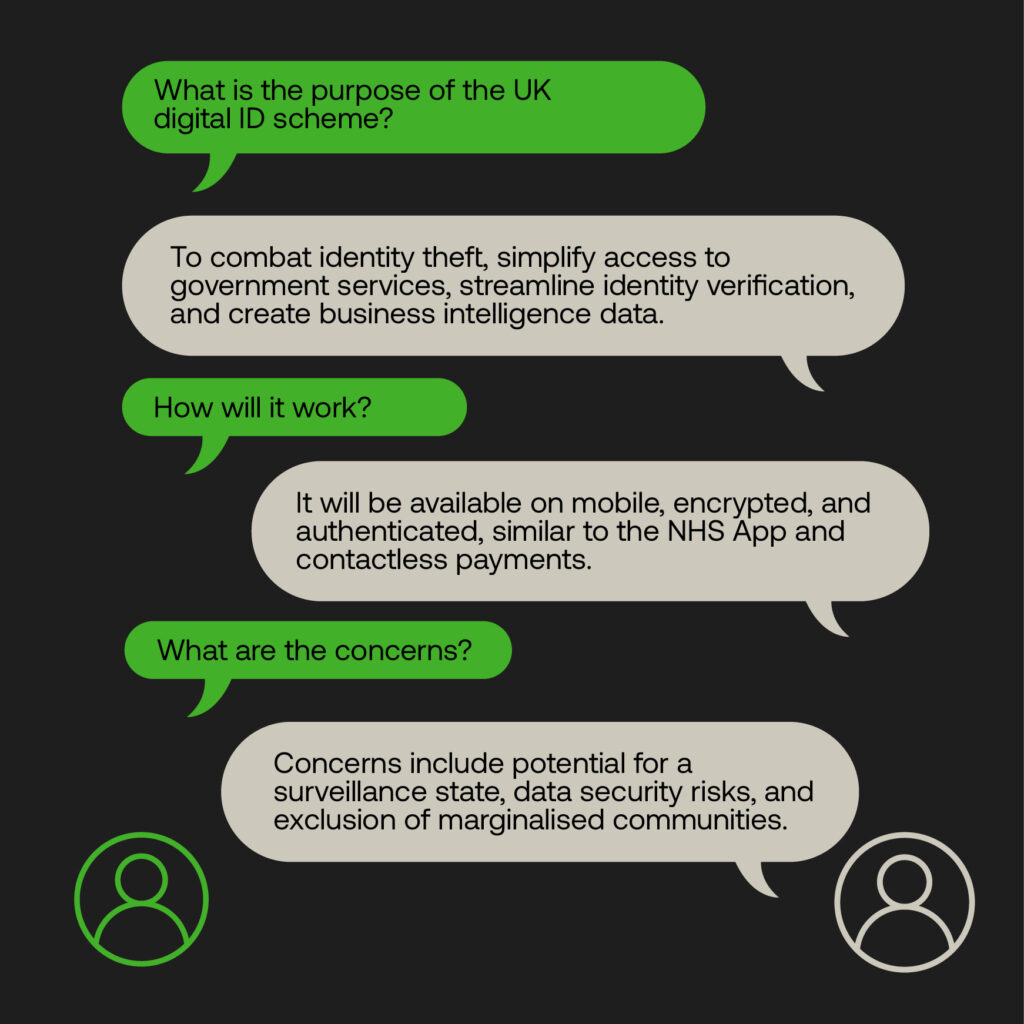

As it currently stands, fraudsters have a fairly simple way to steal identities and pose as others using a National Insurance (NI) Number. In response to combat “illegal working”, this nationwide ID scheme intends to grant UK citizens and legal residents to gain direct access to governmental services, to simplify the lengthy process of complicated identity verification checks (for mandatory Right to Work checks by the end of Parliament), and create intelligence data for businesses.

It’s a step toward digitalised compliance away from siloed paper-based reporting that facilitates document forgery. As millions of Brits have taken to the use of the NHS App or contact payments, the new digital ID will also be available on mobile, encrypted and authenticated to protect transactions. It is similarly intended to “streamline verification processes across private sectors”, including financial services.

This has not been taken as all well and good however, with historical hurdles rearing their head. Voluntary ID cards were proposed during Tony Blair’s Labour term, then scrapped in 2011 by the Conservative/Liberal Democrat coalition government for large expenditure and its intrusive nature – a feeling once again felt by the population and civil liberties groups.

Skepticism around a ‘surveillance state’ sees how the proposal remains opaque about the government’s intentions for storing the data. If contained in one destination, it’s open to hackers; a third of the public are worried about their personal data being used without permission, with a further 31% concerned about it being sold to private companies. Digital IDs may also exclude marginalised communities.

Communication breakdown

2.4 million UK citizens signed a petition against the digital ID cards.

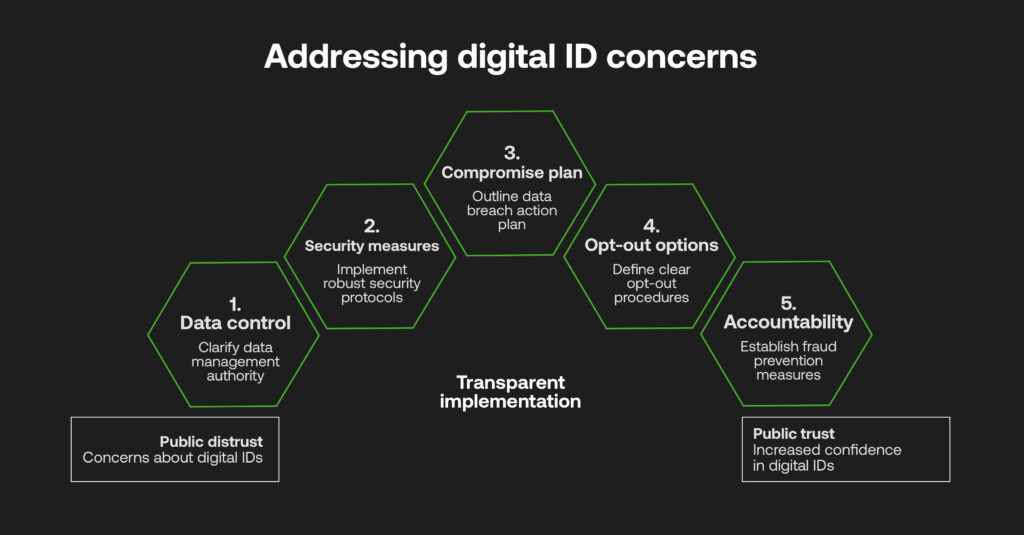

Such is the backlash that over 2.4 million have signed a petition against the digital ID cards, far more than enough to be considered in Parliament. It signals an obvious gulf between those looking to improve data-backed services and the public that will be affected, with a potentially ‘rash’ introduction ignoring consultations and some transparent fundamentals citizens expect in a world more indebted to data privacy than ever before, as follows:

- Who controls their data, be it a governmental department or centralised agency.

- How it is made secure and audited, besides the proposed encryption and authentication protocols that should be baseline requirements.

- Action plans for if the data gets compromised.

- What opting-out will mean, if it’s at all possible.

- The personal accountability factors expected for fraud prevention.

A third of the public are worried about their personal data being used without permission. A further 31% are concerned about it being sold to private companies.

Identity fraud cases may be public and a nationwide concern, but that does not mean that it’s common knowledge to understand hefty data regulations such as the General Data Privacy Regulations (GDPR in the EU, even more so following Brexit), how privacy laws are governed, and how consent is logged and maintained once someone clicks on a website preferences check-box.

Being identified by the government is not the same as being protected, and unclear motives do not improve the public’s awareness or backing of such an initiative.

The problems of ongoing fraud narratives

This move highlights some oversight from the UK government (probably indicative of a worldwide challenge) that public literacy is in line with the rate of innovation. When fraud spikes, it’s assumed that there’s a deep-rooted awareness of it and even its inner workings, therefore justifying the speed with which digital IDs are being introduced––all before the correct safeguards are in place for every intended citizen.

Narratives toward fraud can be considered a scaremongering cover-up for fast tech adoption before any consultation with the general public; a highly reactive “solve it now, explain it all later” mantra. Further down the line, a lack of integrity will likely have already set in. Beyond public scrutiny, the poor implementation of a solution designed to protect sensitive data can lead to worse circumstances if breached, or if the system fails. As financial services can be irrecoverable from limited anti-money laundering (AML) protocols, governments can similarly suffer from lengthy distrust that’s tough to come back from.

It is also simple to see where national digital ID efforts have struggled elsewhere. In South Africa, two million people were unwittingly blocked out of their digital IDs also used for necessary healthcare services. India’s long-running Aadhar scheme has also faced drastic criticism for denial of services to some impoverished peoples, and the threat of compromised mass-collected biometric data. If one piece of this information is deemed illegitimate for a user, it could affect their whole governmental identification record and land them in trouble.

Better readiness, better ID usage

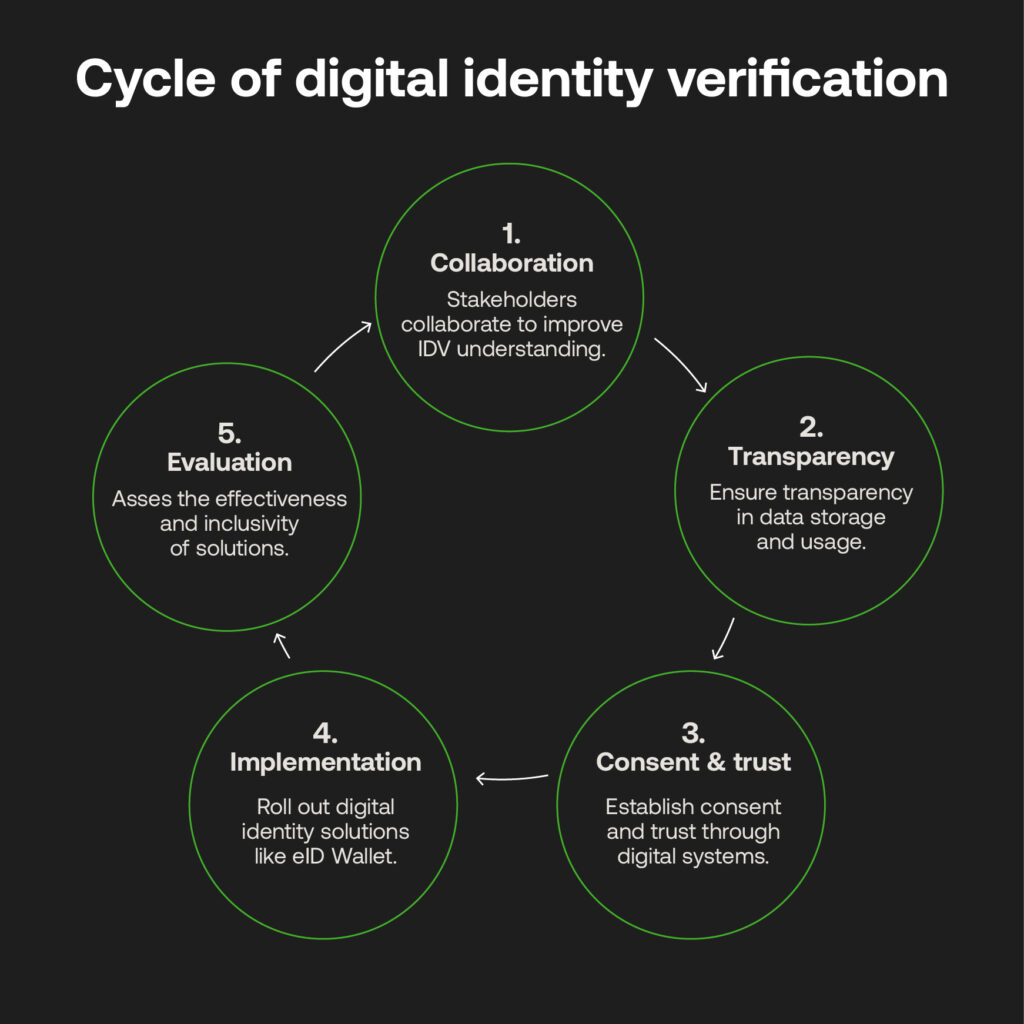

The identity verification (IDV) issue is a minefield here, as personal data is tussled between criminal usage and the protective guardianship of governments, regulators, financial institutions and other non-financial businesses. This highlights a pivotal point: to oppose huge networks of online, undercover hackers and fraudsters, there has to be collaboration to better the understanding of IDV for consumers and companies, transparency around how it is stored and used, and a way to instil consent and trust using a digital system.

The EU’s long-standing physical ID cards are hoping to become an answer to digitalised identification with a 2026 rollout of the Digital Identity (eID) Wallet, enabling citizens access to public and private services both online and offline, to create signatures, and share and store digital documents.

This does not seem too far removed from the UK’s effort. However, its takeup by 350 businesses and public authorities across 26 member states and roadtesting through pilot projects suggests an informed roadmap for how the ‘Brit Card’ proposal should have gone: an evidential and considered approach for it to function as a safe and inclusive piece of technology that serves to stamp out illicit activity.

Taking smaller, informed steps

As a regulatory technology (RegTech) provider, we believe that the next vital stages of digital IDV hinge on greater processes and education. No system, especially one with nationwide reach, can achieve its anti-fincrime goals without a strong compliance culture and framework built around it.

In the UK, immediate digital ID rollouts should prioritise public consultation and clarity around the government’s role and responsibilities, in line with data privacy laws. Only then can an infrastructure be built in light of public support, and a foundation for an anti-fraud future that’s as ethical as it is powerful.

Get in touch with us to learn more about how RelyComply’s looks to close the AML readiness gap in the UK, and take a look at our latest whitepaper Closing the Gaps in Financial Crime Prevention, identifying how building technical bridges between accountable financial institutions through RegTech provides safe, more transparent and accurate AML.