Challenging 5 common Suspicious Activity Report misconceptions

AML would be a far different, and far less effective, tool for fighting crime without the Suspicious Activity Report (SAR). Despite being the backbone to kickstart honed-in investigations into genuine laundering, trafficking, and terrorist financing, SARs are still often misconstrued by the institutions that must utilise them for AML reporting requirements.

The trouble with growing pressure to streamline SAR submission is that their complexity is often overlooked at the basic level. Financial institutions (and other accountable businesses) may know what they are and what they’re used for, but this does not go far enough to make them foolproof forms of intelligence that lead to prosecution.

SAR quality is lacking across the board. But some myth-busting can help evaluate the nuances of putting one together, troubleshoot common challenges, and make sure they have positive implications for global AML reporting and compliance culture. Here, we’ll identify five misunderstood factors for filing SAR forms which also underline their imperative usage, and opportunities for making information-sharing more efficient, as identified in RelyComply’s latest Laundered podcast.

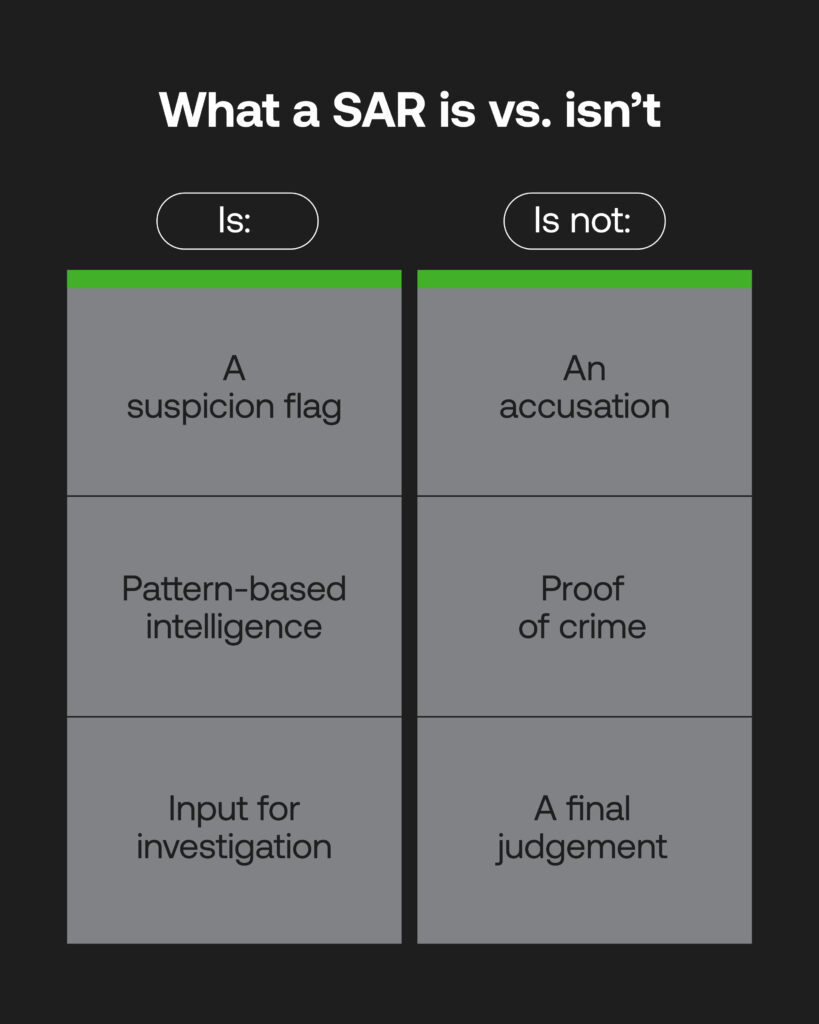

1. A SAR is a suspicion flag, not an accusation

One glaring error is seeing a SAR form as a defamatory alert for the individual(s) involved, who may or may not have done anything wrong. They’re not a legal-binding judgement in any sense; instead, a report of collated data considered outside normative behaviour, which may be indicative of criminal activity.

This distinct payment-related intelligence may not be immediately obvious to law enforcement, hence why there’s an onus on the private sector to be vigilant of any legitimate threats. To financial institutions (FIs), this could be sanctioned peoples banking with them, or signs of siphoned or layered criminal funds.

Any suspicion raised to crime fighting divisions can be vital evidence leading to an eventual arrest, recovering illicit cash, or for use in other targeted investigations. It’s not that FIs have failed in SAR reporting requirements at all by filing a SAR form, and are in fact being proactive to any incriminatory actions, no matter their eventual severity.

As a SAR is an integral document to help understand patterns of criminal behaviour, it unites different public and private organisations to piece together common data. This may be important to vulnerable regions or even a specific event, like a terrorist attack. In the UK, the National Crime Agency’s Financial Intelligence Unit (UKFIU) is responsible for collating and disseminating SARs – where built-up knowledge helps act fast against proliferating organised crime.

2. Poor quality SARs get de-prioritised, or even rejected

The UKFIU receives over 850,000 SARs annually, and with digital transactions volume growing, there’s every chance FIs may slip into a habit of over-submitting reports. There’s a huge amount of time that goes into processing them, where those that lack definitive factors will often be sidelined. Only those with detail will become actionable, essentially.

The triage process is a lengthy bottleneck from start to finish. When a bank or FI submits a SAR, it must be reviewed heavily by compliance teams, financial investigators, company management and legal teams. Inadequate AML systems may expose SAR compilers to false positives, which create error-filled reports to fill and stymy a financial intelligence unit’s (FIU) backlog.

While regulators do desire timely reports, rushing to submit any alerts that exceed SAR thresholds can be counterintuitive. There is complexity around who or why certain transactions take place, more so considering newfound digital asset types, and SARs’ regulatory burden differing jurisdiction to jurisdiction. A lack of understanding around these parameters leads to SARs with vague narratives and context for their submission, which may also hinge on outdated data.

Fewer, and greater quality SARs, have been identified in the UK (potentially due to digital SAR portals, and technological advancement in AML), but such improvements must continue to fight fresh threats from cryptocurrencies and ledgers rife with criminal innovation.

3. SARs come from a range of contributors

It’s easy to see SARs as an intelligence tool reserved for large banks that process swathes of payments. However, SAR filing requirements now apply to fit the diversified financial marketplace, and outside of it. Away from lenders, mutual fund brokers, credit unions or payment providers, there’s cryptocurrency platforms, insurance firms, precious metal dealers, casinos, and other non-financial businesses involved – anyone working in regulated and non-regulated sectors must make a SAR if they’re suspicious of laundering activity.

This is less unusual than many would think, given the levels of access such businesses pose to opportunistic villains. Fraud and laundering rails are getting more numerous and complicated. They can flush cash through luxury goods, or utilise mule victims to open accounts at various firms who may differ in their AML maturity. Crypto mixers and AI-powered biometric hackers can exploit any KYC onboarding faults, where some FIs may not have such crimes on their radar. Ignoring such prevalent SAR narratives can be devastating, as initial crime can lead to other heinous acts such as human and wildlife trafficking.

The diversity of the financial field is not just a boon for consumers that can access the economy more easily, or maybe more cheaply. If every regulated industry is united in taking accountability for producing appropriate SARs for investigations, it covers many gaps in the system where criminals currently lurk.

4. One SAR can fuel cross-border information sharing

SARs are often far from one-off reports for isolated incidents; a single SAR could be used multiple times, including at HMRC for tax purposes, or by a police fraud team. When shared to the correct FIUs and law enforcement agencies, they can be distributed even further to cover multiple jurisdictions and worldwide criminal networks. These complex investigations rely on corroborated SAR information that can help freeze assets, or uncover and arrest widespread organised groups.

In an age where data privacy and customer information is bound by law, being able to facilitate SAR sharing may feel increasingly difficult. Likewise, SAR reporting requirements (UK) will be different from, say, the USA or South Africa (involving FinCEN and the Financial Intelligence Centre, respectively). But though data legislation will vary, cross-border AML reporting requirements and obligations do have similarities, focused on cooperation where shared intelligence can clamp down on borderless crime. FIUs act as bridges for SAR usage, and institutions such as the Egmont Group allow them to be shared internationally to confidently battle predicate crimes.

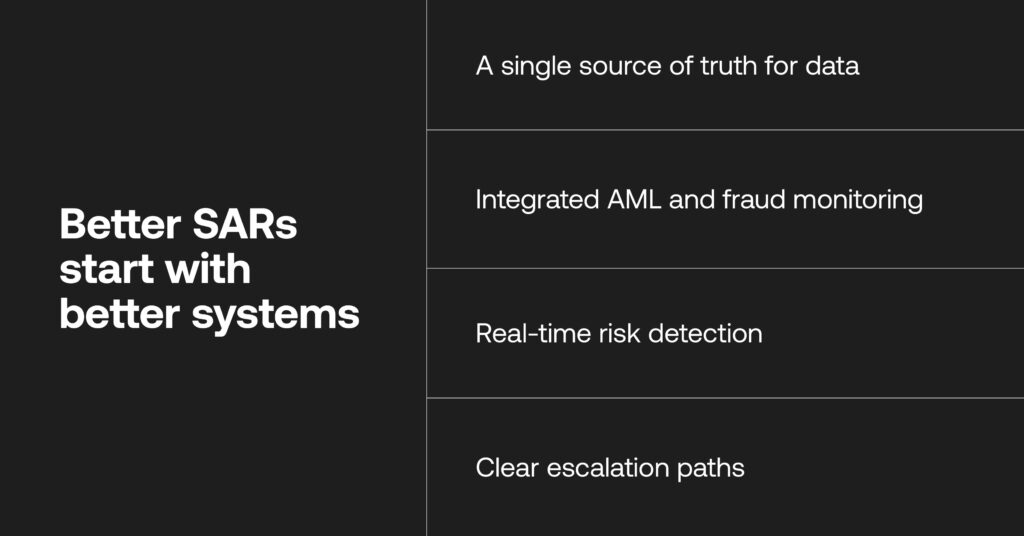

5. Detection is a larger problem than filing a SAR form

Being able to manage proper SAR reporting comes down to the data businesses house. With legacy systems, the downstream reporting stage becomes a problem without a connected, single source of truth for AML investigations. AML and fraud teams often work independently, and the detection of suspicious activity patterns can be missed on both sides, or investigations are performed concurrently with varying end goals.

For SARs to cohesively track transactions and behaviours to entities, an AML system has to run off of an integration monitoring and risk-scoring procedure that unites both teams. That way, any high-risk triggers of SAR thresholds can be raised in real-time, and corroborated to an FIU for further action. When there’s no discrepancies and low-risk activity continues, there’s a reduced chance of cautious filings that are inefficient and, in the long run, slowing an FIU’s processing unit to a halt.

This does happen if an organisation submits SARs to cover every base for fear of regulatory clapdowns, or if they lack knowledge around new criminal typologies their AML systems cannot detect accurately. Greater cooperation beyond shared SAR data needs to happen, be it through tech sprints, AML sandbox development with RegTechs, industry expertise events, internal audits, and education around AI-driven compliance and jurisdictional data privacy laws.

Less fragmentation means better SAR protocols

The appetite for more close-knit cross-border intelligence is there despite obvious nuances to SAR reporting procedures. What’s needed to achieve it is optimised real-time detection for common laundering or fraudulent techniques, in line with anti-fincrime recommendations – and ultimately what will get law enforcement having the right eyes on the right criminals as quickly as possible, as follows:

- Set appropriate risk thresholds: consistent flags of suspicious activity raises the likelihood of catching actual criminals, and lowers time spent on false positives.

- Establish internal escalations: a single AML system can simplify the real-time routes for investigating behavioural anomalies, for enhanced due diligence and eventual reporting.

- Centralise analytics: contextualised investigation notes, tracked data and integrated AML and fraud systems help to build stronger case narratives for SARs.

FIs in the UK and abroad all must maintain vigilance and accountability in finding any actions worthy of investigations. With that, they play their ever-important role in stamping out financial crime at the source and seeing criminals actually prosecuted.

A suspicious activity report should not be feared. Instead, better guidance on what makes for quality detection and case management will see more reports that unite the entire ecosystem, and when SAR submission breeds success in law enforcement, consistent and ongoing risk monitoring can continue to advance in line with criminal evolution – when we need it most.

To find out more about the prominent role of SARs in the UK’s law enforcement, listen to our Laundered podcast episode featuring Gareth Dothie, Head of Bribery and Corruption at City of London Police.