UBO risks: The hidden link between tax crime

Table of Contents

Tax evasion is a drastic action often well beyond mere ‘avoidance’. The illegal dodging of tax payments costs countries half a trillion dollars a year, all because individuals and companies preemptively exploit tax loopholes for financial gain. While tax evasion is already a crime, the veiling of identities or payments often covers other areas of criminality that organised networks may carry out to avoid detection or even businesses looking to avoid reputational damage.

Auditors are on high alert during the necessary time for filing tax returns. South Africa’s financial institutions must also step up their anti-money laundering protocols to identify obscured information, such as beneficiary control, complex structures, and offshore accounts used to conceal taxable profits from the authorities.

Regulators are not chasing and scrutinising individual offenders. Instead, their tractor beams are on the overarching systems, letting tax-related crime happen through faulty compliance measures. Every financial institution is liable, with advanced efforts needing to be made to account for evolving evasive methods.

The tools of obfuscation (and why they work)

Traditionally, tax-related offences and money laundering have been treated as separate entities, as outlined in an IMF report. This caused avoidance in reporting suspicious tax payments to anti-money laundering (AML) regulators, until the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) designated tax crime as a predicate offence in 2012.

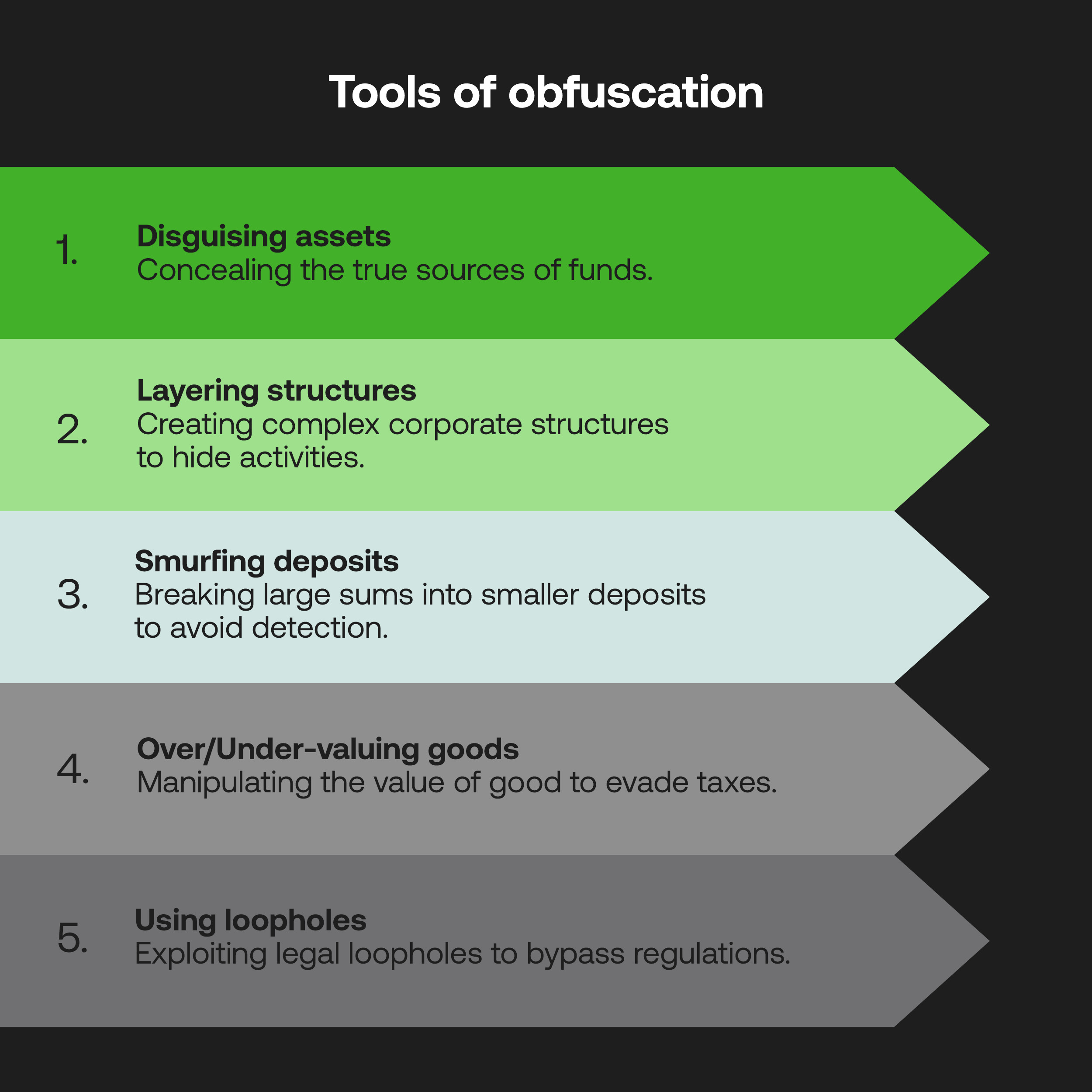

There are many connections between laundering methods and tax evasion: disguising the sources of assets; layering corporate structures; smurfing deposits; over- or under-valuing goods; purchasing long-term investments; and using intermediaries, offshore tax havens and cross-border compliance loopholes to slip between domestic AML laws. Often, laundering will be carried out using funds owed for tax reasons, hence AML approaches become paramount for the tax community to discover hidden threats within legal facades.

However, each country can technically determine what counts under the tax crime umbrella. This creates a massive gulf in how nationwide institutions conduct their due diligence during customer or business onboarding, or aim to spot suspicious activity among millions (if not billions) of cross-border payments. Neither traditional AML processes nor lack of regulatory oversight can fight obfuscated holding structures, only becoming more crafty with evolving technology and letting tax-related crime proliferate.

The hidden layer of tax evasion: UBO obfuscation & shell companies

While FATF’s frameworks for bettering financial institutions’ know your customer or business (KYC/B) processes are in place and many regulated entities meet requirements, ultimate beneficial ownership (UBO) structures are often opaque and are not thoroughly interrogated.

Following the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission’s (CIPC) amendments to the Companies Act in 2023, a UBO is defined as a natural person with at least 5% beneficial interest or control. They may not reveal their identities for multiple reasons, such as to avoid cyber or physical threats or to hide partnerships and business strategies from industry competition.

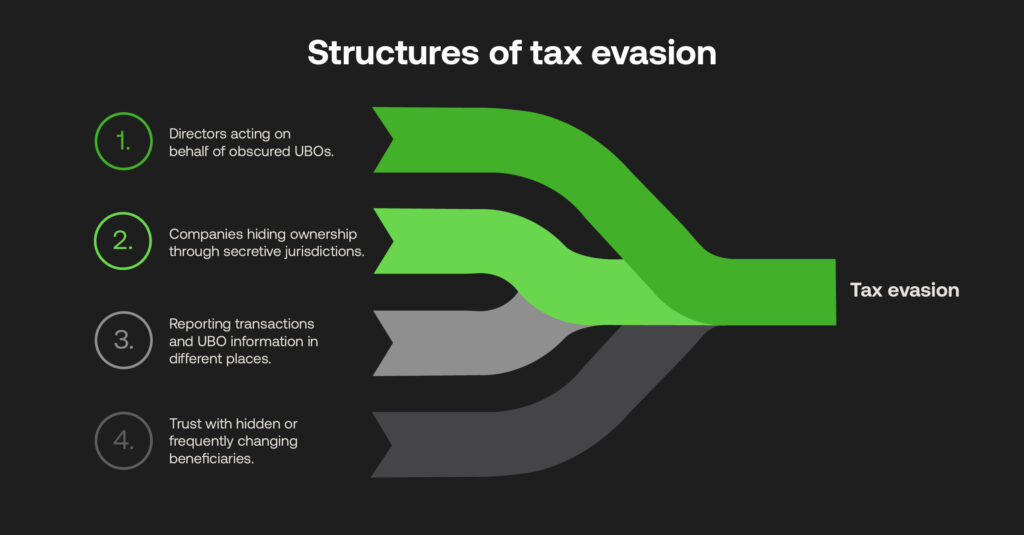

Common tax evasion structures applicable to UBOs include:

● Nominee directors and shareholders: Those that are legally registered, but act on behalf of others that are obscured.

● Intermediary shell companies: Businesses registered in secretive jurisdictions to create distance between the company and the owner.

● Misaligned jurisdictional activity: Transactions or tax filings are reported in one place, and UBO information is reported in another.

● Complex trust structures: Where beneficiaries change frequently, or remain hidden altogether.

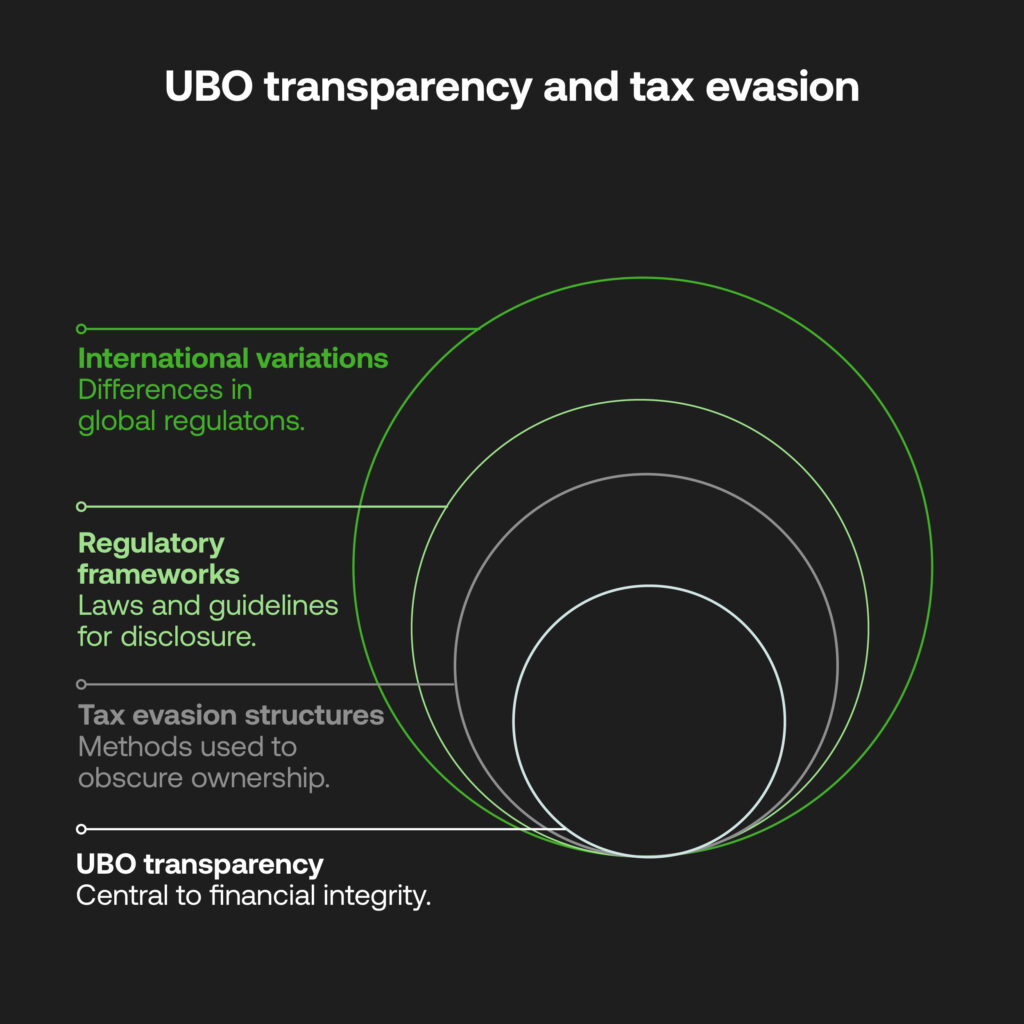

It’s also more achievable for evasion to operate across multiple jurisdictions with differing UBO disclosure agreements. In the US, the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) requires some companies to disclose this information to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network to FinCEN. Regulations differ among APAC countries, and the UK has three registers. The UAE obliges corporate entities to disclose UBOs.

At the same time, the EU reneged on its plan for member states to set up public UBO registries when the European Court of Justice ruled it a privacy breach in 2022 since the EU’s Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD) has addressed strengthened register usage, made available to those with vested interest such as journalists, law enforcement, or supervisors. In South Africa, the CIPC instead followed its intention to establish a central, non-public BO registry available to regulators and law enforcement professionals.

Regulators leading the way

It will take a more transparent approach to UBO registers for financial institutions to assess complex business structures as part of KYB, which raises risk in areas such as tax evasion or money laundering. Initiatives are not global, but FATF has revised its definitions and recommendations on “beneficial ownership”, “beneficiary,” and “legal arrangements”, and the OECD aims to improve the collaboration and sharing of suspicious transaction reports (STRs) between tax companies and AML authorities.

In that light, regulators are scrutinising compliance systems more closely to connect the dots between businesses, individual entities and payments, rather than UBO identification being a background compliance tick-list task. Understanding if declared UBOs are who they say they are, unearthing shell layers, and flagging operations in known tax havens all take advanced data processing and intelligence sharing that are integral to institutions’ modern AML capabilities.

Tax authorities are setting the standard for deploying AI-driven tools to deal with tax evasion cases. The IRS utilises the technology to identify error-prone tax returns, and the UK’s increased risk-based approach is shown through HMRC’s software, which draws parallels between unrelated data and spots potentially suspicious income and lifestyle mismatches.

SARS has been utilising machine learning algorithms to identify taxpayer discrepancies since 2016. With around R800 billion of revenue remaining uncollected, AI plays a major role to build on SARS’ success, namely recovering R91 billion and identifying over 30,000 unregistered taxpayers.

A route to AML partnerships

Institutions can no longer utilise the ‘tax excuse’ for poor reporting, particularly under legal STR obligations where tax evasion has been mandated as a predicate offence in the FIC Act. Tax may technically be a legal challenge, but its relationship with financial crime makes it an imperative business operation.

It’s one thing to detect any risky business structures during KYB, and it’s another to present a transparent audit of the investigation to AML authorities. RegTech platforms are built to automate risk monitoring and reporting, attuned to jurisdictional rules and assist regulated entities in finding hidden threats among the noise with flags made known to compliance teams instantly, around the clock.

With a flexible platform built for customisable risk thresholds, institutions can verify corporate data against the CIPC BO registry as well as trusted global registries, sanctions, PEP, and tax crime lists. This assists in mapping hierarchies, and flagging missing or conflicting UBO declarations, and to rate entities operating in high-risk jurisdictions low in tax transparency, AML enforcement, and evasion risk.

Tax evasion is a serious offence and has been detrimental to the AML efforts of governments, regulators and businesses all around the globe. Collaboration around the need for risk-based tax compliance solutions is gathering steam, but prevention success will not continue if UBOs can remain under the radar. Greater data transparency matched with AI-driven AML systems may be the answer, where tax authorities are leading by example to clamp down on this ever-pervasive financial crime.

Disclaimer

This article is intended for educational purposes and reflects information correct at the time of publishing, which is subject to change and cannot guarantee accurate, timely or reliable information for use in future cases.